Episode 1: Inferno Crisis

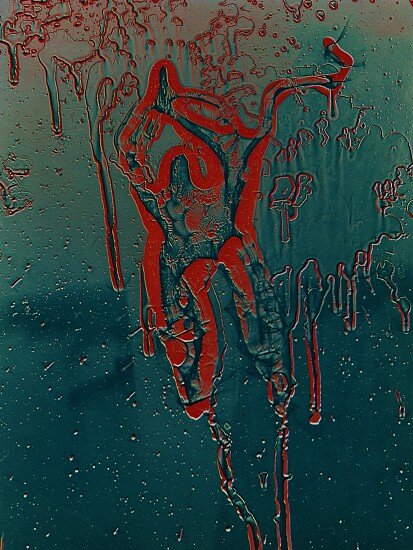

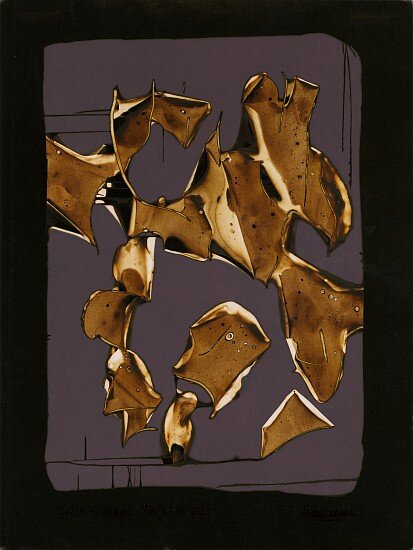

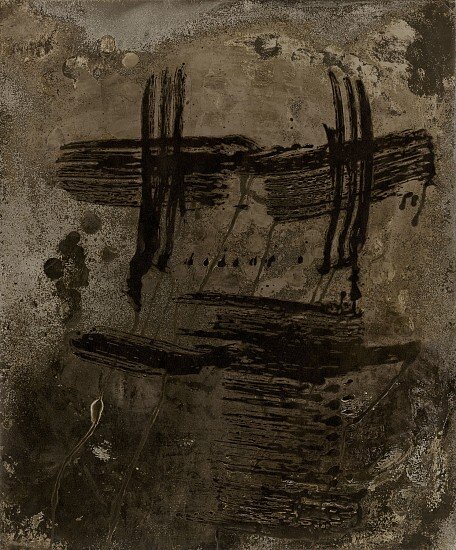

In Episode 1, we discovered that August Strindberg’s celestographs were not, as he thought, photographs of the night sky. They are chemigrams, or images that are a result of chemicals mixing with the photographic emulsion on the surface of the metal plate or paper as well as other environmental influences, like dust or whatever else is floating through the air. The weather has something to do with it as well. Although not what Strindberg believed them to be, they are mysterious and beautiful.

Many artists have experimented with chemigrams since then, using the unique properties of various chemicals to create abstractions, including Chargesheimer, Henry Holmes Smith, and Pierre Cordier. Gallerist Tom Gitterman has done a great deal of work to promote these photographers. (All images below courtesy Gitterman Gallery)

In this episode, I mentioned the first photo of the star Vega, which was taken on July 17, 1850 with an exposure time of 20 minutes. It was taken by astronomer William Bond and John Adams Whipple at the Harvard Observatory.

Bond and Whipple, Vega, daguerreotype, 1850. Image courtesy Harvard University.

Sir John Herschel, the mathematician, astronomer, botanist, chemist, and inventor of the cyanotype process, was photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron several times. I had the pleasure of handling her captivating portrait of him in 1867 at Sotheby’s in 2019. It is signed by Herschel himself in the lower center of the mount.

Julia Margaret Cameron, J. M. W. Herschel, albumen print, 1867. Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Herschel’s primary, monumental gift to the history of photography was the invention of the cyanotype, and his own cyanotypes can be found in the renowned Gernsheim Collection at the Harry Ransom Center.

The Honourable Mrs. Leicester Stanhope, cyanotype, 1836. Image courtesy the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

August Strindberg was was a complicated person, and it sounds like he was, in many ways, flawed. Despite the human shortcomings, his contributions to theater, literature, and photography are many.

August Strindberg, Self-Portrait, undated (likely before 1900)

Certainly it is easy enough to disregard Strindberg’s more outlandish claims and conclusions. It is less easy to dismiss the complex forces that directed his thinking. Rational and irrational, mad and tame, they emerge from the profound questions that are within photography itself: What is the relation between appearance and meaning? Does photography offer impartial knowledge or a surface for imaginary projection? Does it have any value outside of conventional uses? These are questions that neither art nor science have entirely contained. Strindberg may well have grasped over a hundred years ago that they never would.- David Campany, August Strindberg: Painter, Photographer, Writer, 2006

and finally…

I highly recommend the short films featuring the animated duo of morose August Strindberg and his floating pink pal, Helium.