Episode 25: Shades of Gray

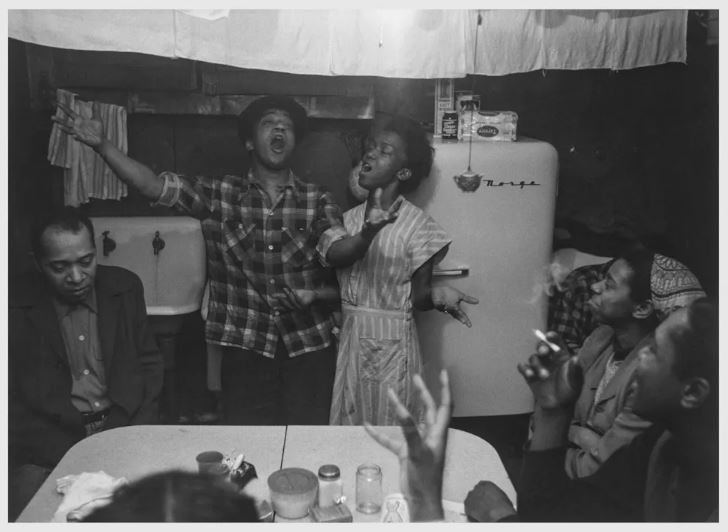

“I want to photograph Harlem through the Negro people. Morning, noon, night, at work, going to work, coming home from work, at play, in the streets, talking, kidding, laughing, in the home, in the playgrounds, in the schools, bars, stores, libraries, beauty parlors, churches, etc.” -Roy DeCarava quoted in Roy DeCarava: a retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, 1996

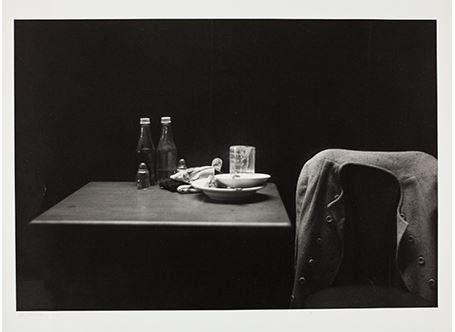

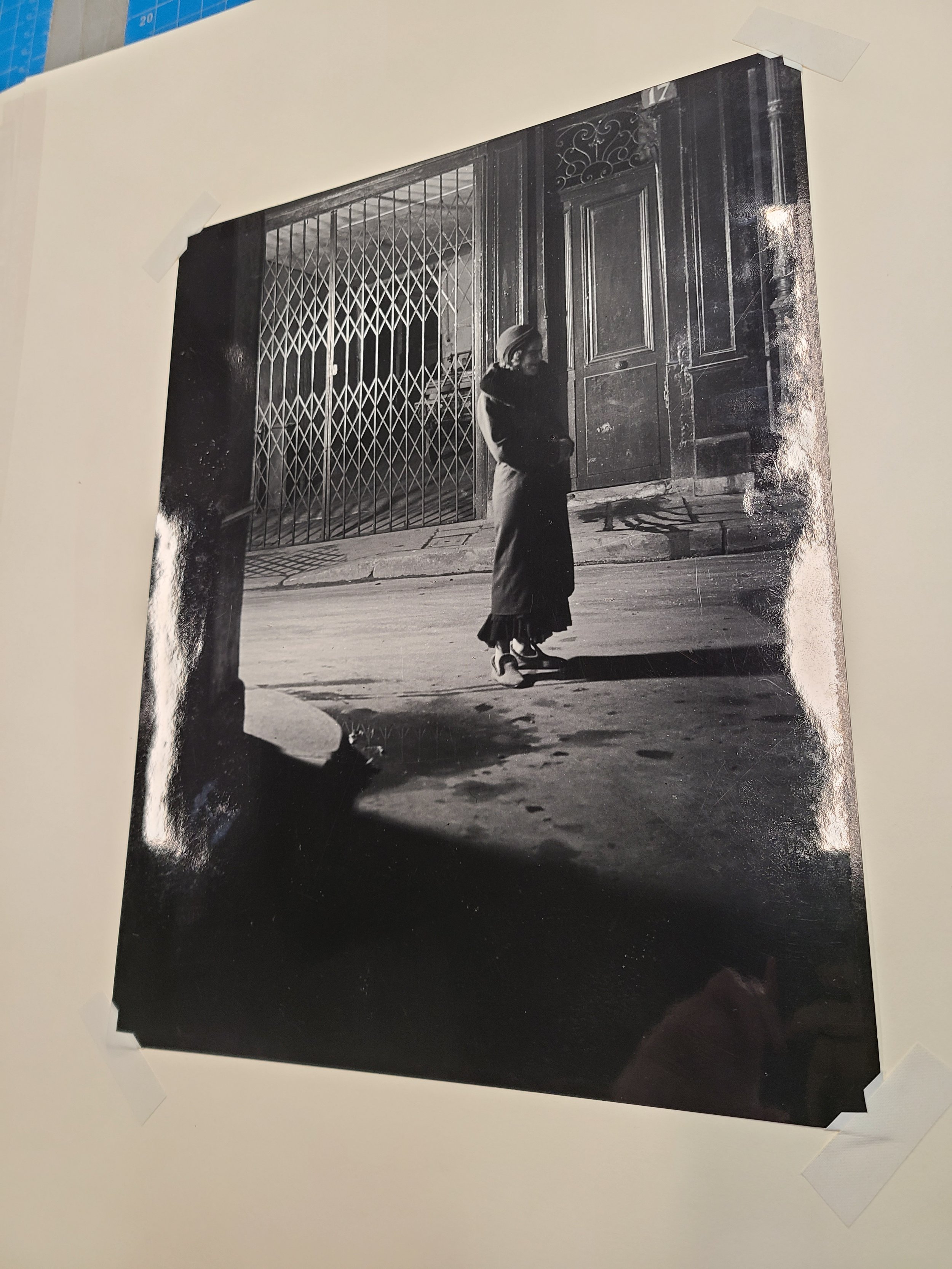

In this episode, I talk about one of my favorite photographs by Roy DeCarava, shown below.

Roy DeCarava, Dancers, 1956, Sold at Sotheby’s, 21 April 2021 for $40,320

When I started researching this print, I noticed that other prints were not made nearly as dark as the one we were selling. For instance, a print from the same negative is at the Art Institute of Chicago, but a lot more detail is visible:

Roy DeCarava, Dancers, 1956, Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

This got me thinking about the choices we make as photographers, and why we make those choices. Just as I started contemplating this question, by coincidence I was introduced to Saul Robbins, who was a graduate assistant for DeCarava at Hunter College.

Saul is a photographer himself, and has a lot of great insight about what it was like working with DeCarava and the influence he had on his own work and teaching style. Robbins’ work has been exhibited and published internationally, most recently Harvard Business Review and Der Spiegel. He holds an MFA from Hunter College (City University of New York) and is Adjunct Professor of Photography at The International Center for Photography, New York Film Academy, and The School of Visual Arts. Robbins also consults privately and leads Master Workshops about communication strategies and professional development.

Roy DeCarava, Self Portrait, Reflection (1949)

Roy DeCarava was born in 1919 in Harlem right before the explosion of arts and culture of the Harlem Renaissance. He enrolled at Cooper Union, but, after two years of hostility from white students, he left and enrolled instead at the Harlem Community Art Center to study painting.

Edward Steichen, then curator of the Museum of Modern Art, attended DeCarava’s first solo show at the Forty-Fourth Street Gallery in 1950 and bought several prints for the museum’s collection. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1952, the first African American photographer to receive the grant. Many of the photos enabled by this $3,200 award were compiled in the book The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955; reissued 1988), with text written by Langston Hughes.

DeCarava’s interest in education led him to found A Photographer’s Gallery (1955–57) and a workshop for African American photographers in 1963. Many of DeCarava’s jazz portraits were published in The Sound I Saw: Improvisation on a Jazz Theme (2001).

His first solo museum exhibition, ‘Harlem on My Mind’ was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969. In 1996 the Museum of Modern Art organized a DeCarava retrospective that traveled to several cities and introduced his work to a new generation. DeCarava received a National Medal of Arts in 2006.

Roy DeCarava died in 2009 at the age of 89.

The Shirley Card, first used by Kodak, is a fascinating facet of photographic history. The podcast 99% Invisible has done a fascinating in-depth episode on these cards and the evolution of film through the years.

Shirley cards through the years, notably with the word “NORMAL” by each model’s face.

1966 Shirley Card

1996 Shirley Card

Episode 24: Denise Bethel, Part I

For this episode, I sat down with Denise Bethel to discuss the first part of her education and first jobs, including the incredible 10 years she worked at Swann Auction Galleries.

Denise is originally from Virginia. She did her undergraduate degree at Hollins College, in Roanoke and in 1973 she headed to London to study 19th Century British Painting at The Courtauld Institute of Art. Back in the United States, she worked as the Curator of The Poe Foundation in Richmond, Virginia from 1975-79. She joined Swann Galleries in 1980. Swann had started a Photographs department in 1976, but she was responsible for the major changes in handling Photographs throughout her decade there.

Some individuals that were influential in the market at that time were David Margolis, cataloguer at Swann in the 1970s (and for Denise’s first few sales at Swann) and Edwin Halbmeier, Senior Cataloguer in the Book department, who was responsible for the important 1952 auction of the first American auction dedicated to Photographs: A Panoramic History of the Art of Photography as Applied to Book Illustration From Its Inception Up To Date: The Important Collection of the Late Albert E. Marshall of Providence, R. I.

The First Complete Auction of Photographica in America

Sources Denise used for references at the time included American Book Prices Current and The Photograph Collector.

In 1985, she handled books from the Estate of Lee Witkin, including an extra illustrated edition of Henry James’ A Little Tour of France with platinum prints by Frederick Evans for $30,000 (hammer). That fall, she sold a circa 1851 daguerreotype of Mathew Brady, his wife, Juliet ‘Julia’ Brady and Ellen Brady Haggerty for $54,000 (hammer) to the National Gallery. Those were the top lots for 1985 for any auction house.

Scan from the November 14, 1985 auction catalogue

70 years ago Swann held the first-ever photography auction in the United States. Panalists include Deborah Rogal, Director of Photographs at Swann, Denise Bethel, and Daile Kaplan. This special program occurred on February 7, 2022.

Episode 23: Layer Cake

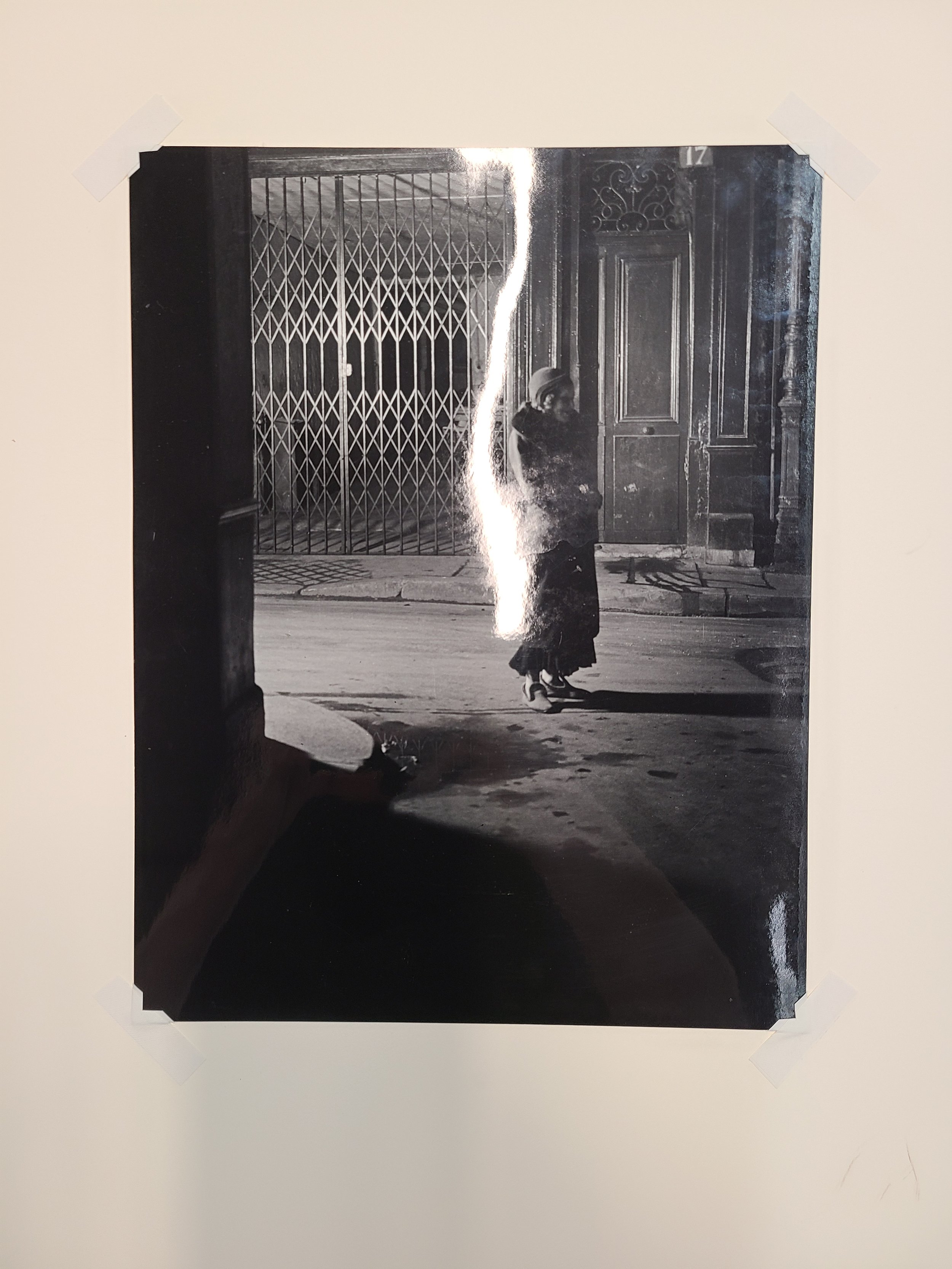

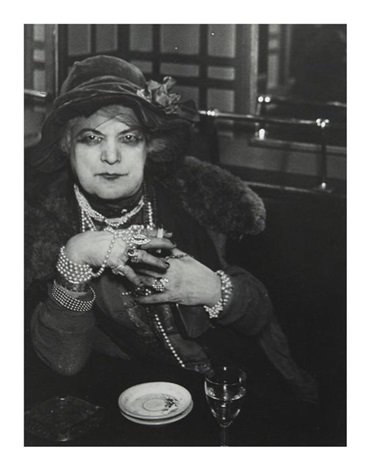

Brassaï took three photographs of a woman named Madame Bijou in a bar called Cafe du Lune in 1932. She was a mysterious woman also known as La Môme Bijou. She has inspired playrights, film directors, and artists through the years although very little is known about her.

Director James Cameron’s pencil copy of Brassaï’s photograph was featured in a scene in his hugely successful film, Titanic.

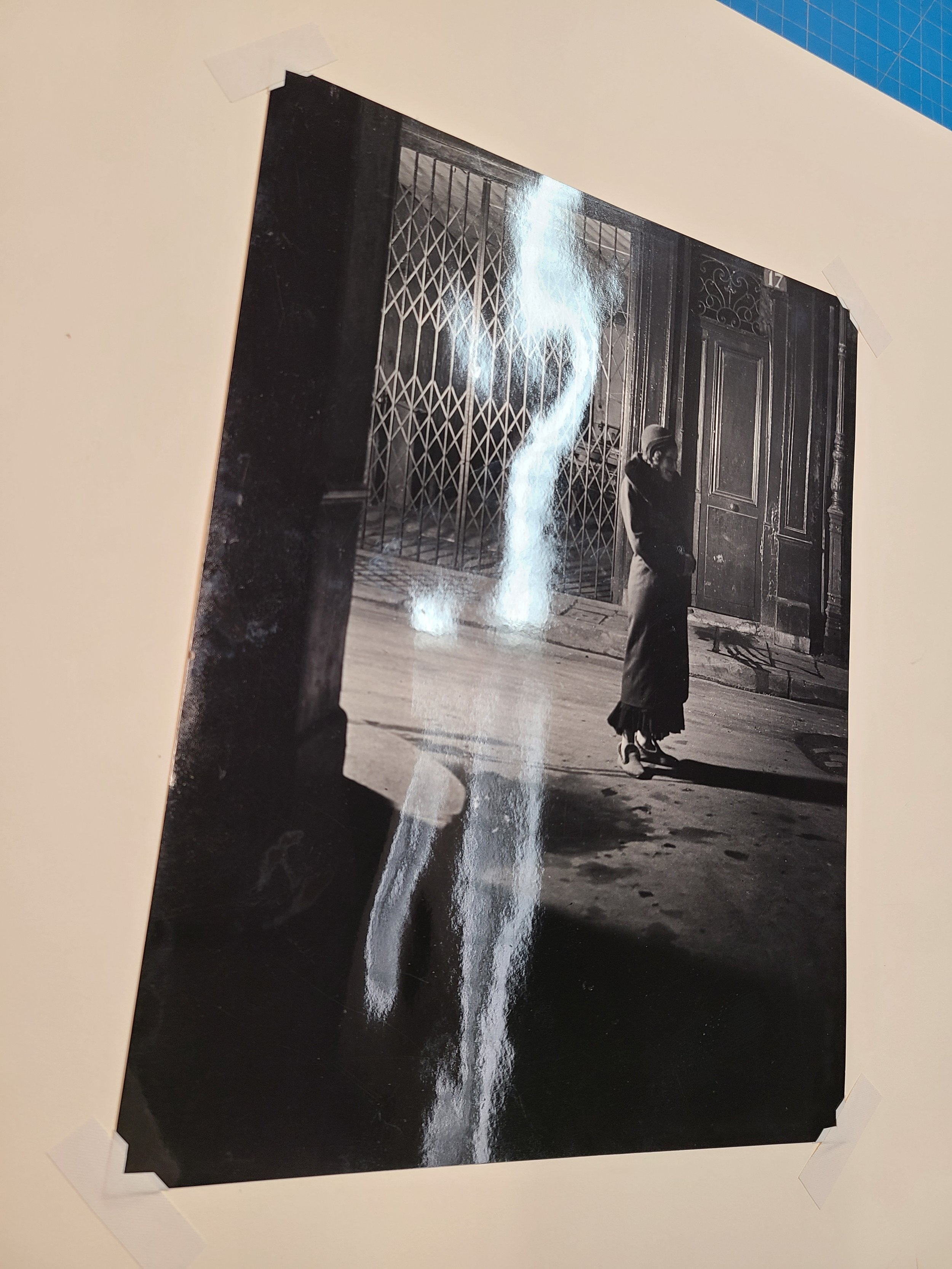

Brassaï was skilled at darkroom tricks. This photograph was created by blacking out the right side of the negative so that it appears as if one of the gang members are looking at the photographer behind a wall.

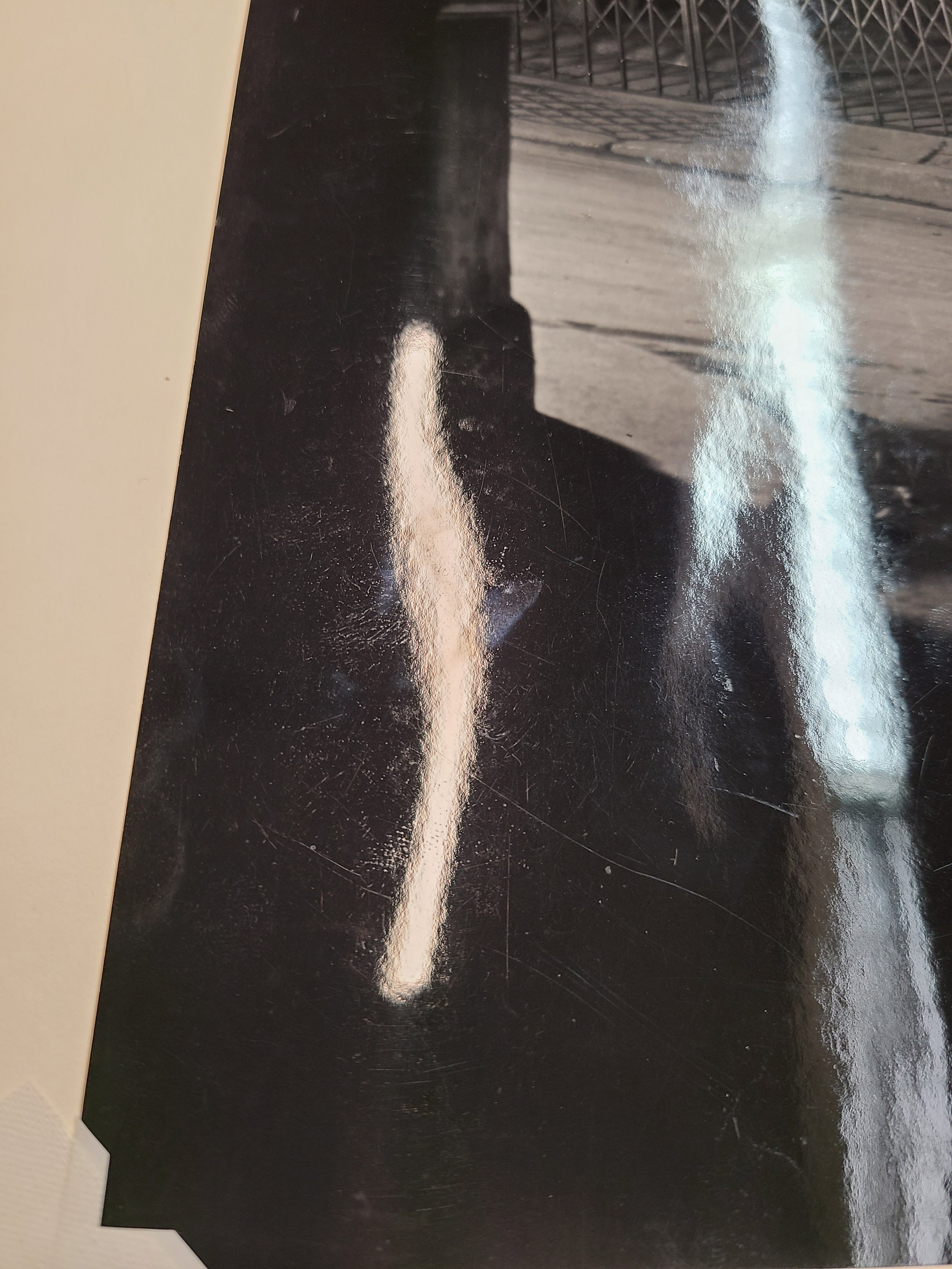

This photograph, taken in 1931 but likely printed later, has been ferrotyped. This process gives the surface of a photograph a highly glossy appearance, which Brassaï favored. However, it is believed that he was using his dressing mirror as a surface for drying his prints, so any dust or scratches on the surface of the mirror would transfer to the print itself. Additionally, if part of the print tried faster than the rest, a mark would appear on the surface as well. It is very common for Brassaï’s prints to have tiny pits, scratches, fingerprints, and/or a tell-tale strip at the perimeter that appears matte compared to the rest of the print.

A wonderful tutorial on making ferrotyped prints can be found here:

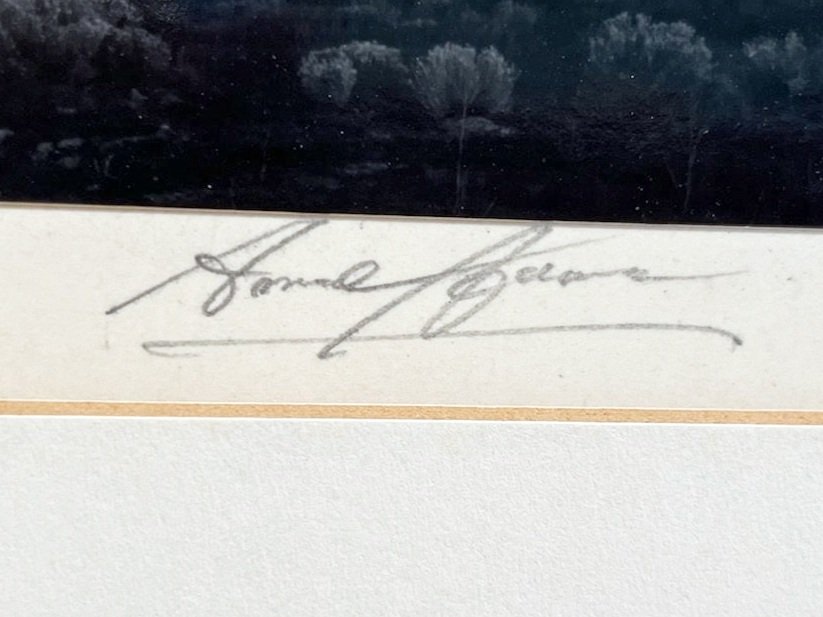

Episode 22: A Conversation with Howard Greenberg

In this episode we get to know Howard Greenberg, one of the most influential photography dealers in the world. He tells us about his beginnings as a young man getting his first camera, to the treasures he sourced out in the Woodstock area, to the growth of his gallery in New York.

From the HGG Website:

“The foremost commitment of Howard Greenberg Gallery is to extend an awareness of and appreciation for fine art photography. Accordingly, we are fully accessible to the beginning collector and able to assist and inform the experienced connoisseur and institutional collector.”

In 2019, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston announced the acquisition of the Howard Greenberg Collection of Photographs, funded by a major gift from the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Charitable Trust. Carefully assembled over more than three decades, the collection comprises 447 photographs by 191 artists, including rare prints of modernist masterpieces and mid-20th-century classics.

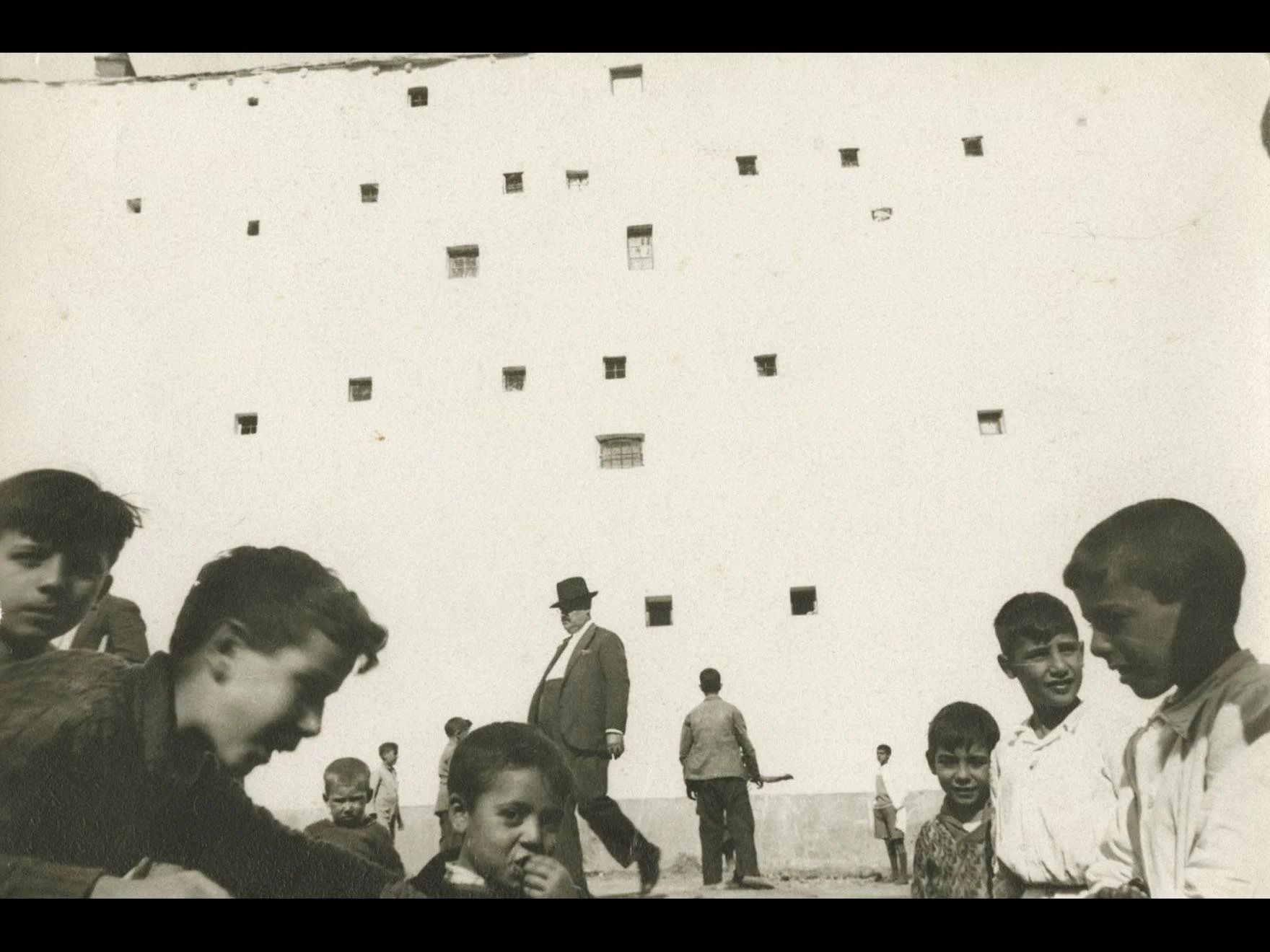

Highlights of the Howard Greenberg Collection are a group of key photographs—including Madrid, Spain (1933)—by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who championed the concept of capturing the “decisive moment,” as well as works by Robert Frank, Leon Levinstein, Ralph Eugene Meatyard and James Van Der Zee. The collection also holds major works by master photographer Edward Steichen, including his striking 1924 portrait of Gloria Swanson draped with a lace veil. In addition to classic works by prominent American photographers such as Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model and Margaret Bourke-White, the acquisition contains powerful photographs by Mexican, Czech and Hungarian artists Manuel Álvarez Bravo, André Kertész, Josef Sudek, Jaromir Funke and Imre Kinszki.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Madrid, Spain, 1933

Episode 21: Post-sale Wrap with Aimee and Emily

On May 2, Sotheby’s concluded the first part of a landmark multi-auction sale series for Pier 24 Photography from the Pilara Family Foundation, achieving an astounding $10.6 million – nearly 120% of the combined presale high estimate – with two thirds of lots outpacing their presale high estimates to benefit the Pilara Family Foundation in support of charitable initiatives in healthcare research, education, and the arts.

The exceptional sale results, attracting bidders from 23 countries, reinforce the unprecedented depth of the Collection, charting the historical intersection of modern art and photography and reflecting the power of the image in contemporary culture.

The two-part single-owner sale set numerous new benchmarks and auction records, including for Robert Frank, whose renowned Charleston, S.C. attracted the highest number of bids (32), leading the sale series for a total of $952,500 and shattering Frank’s previous auction record. Robert Adams’s Selected Images from Eden, Colorado marked another artist record, achieving 130% of its presale high estimate for a total of $330,200.

Robert Frank, Charleston, 1955, sold for $906,000, a new record for the photographer. (presale estimate: $250,000-350,000)

Other notable accolades for the collection include new records for a singular work from Richard Avedon’s In the American West series for Juan Patricio Lobato, Carney, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980 and Clarence Lippard, Drifter, Interstate 80, Sparks, Nevada, August 29, 1983, both of which yielded 150% of their presale high estimates, each realizing $444,500 as well as a record for the highest price for a portrait of Bob Dylan from Bob Dylan, Singer, New York, New York, February 10, 1965, which trounced the previous record by more than double; Deborah Luster, whose One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana more than tripled its presale high estimate for a total of $101,600 in her auction debut; Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, which realized $609,600, marking a new record for the iconic image and the second highest price for Lange overall.

Auction records were also achieved for Larry Clark, Shomei Tomatsu, Katy Grannan, David Goldblatt, Bruce Davidson, Wright Morris, Josef Koudelka, and Erica Deeman, who made her auction debut.

Lot 1 from the auction, Robert Adams’ ‘Pikes Peak’, sold for $95,250 (presale estimate $30,000-50,000)

The inspiration for the Collection began in 2003, when the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) presented a groundbreaking retrospective of the work by renowned artist and photographer Diane Arbus. It was in this landmark exhibition that Andy Pilara found himself taken by the medium, absorbed by the emotional intensity of not only Arbus’ work, but also with the visceral power of photography and image-making. The experience would inspire Pilara and his wife Mary to acquire their first photograph, a Diane Arbus, marking the genesis of a collecting journey spanning nearly two decades during which the Pilaras would build one of the most comprehensive and significant collections of 20th century and post-war photographs ever assembled.

Pier 24 in San Francisco.

In 2010, the Pilaras opened Pier 24 Photography—a world-class exhibition space located on San Francisco’s Embarcadero. As a testament to their dedication as photography collectors and their philanthropic spirit and desire to giving back to their community, Pier 24 Photography was free and open to the public. Designed to showcase their expanding collection through a rotating program of curated exhibitions, Pier 24 welcomed not only the global photography and fine art communities, but also opened its doors to school children and students, while providing critical resources to emerging photographers through a visiting artist program, commissioned projects, and other awards.

Sotheby’s continues it’s sale series from the collection in October 2023.

Episode 20: The Limits of Control

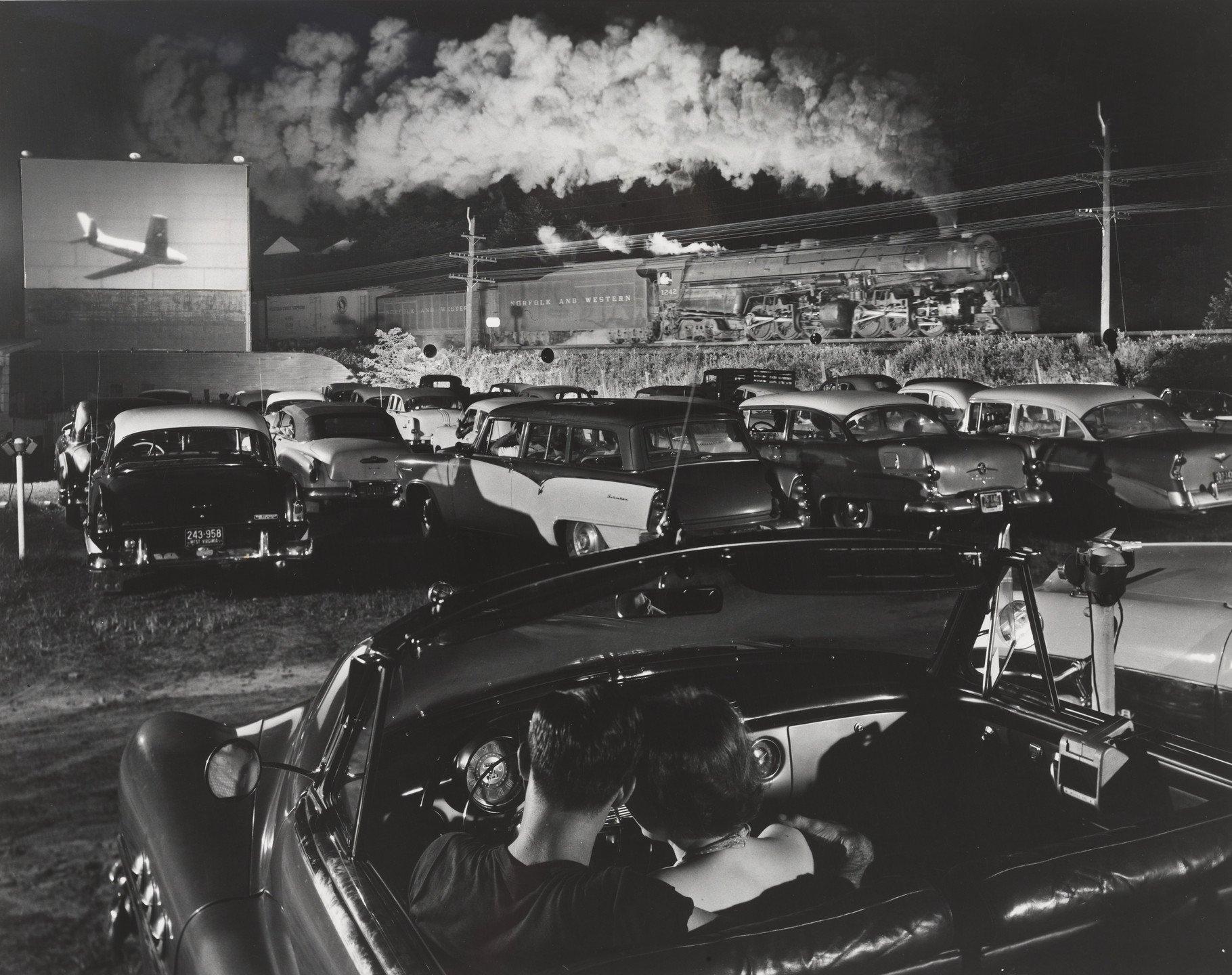

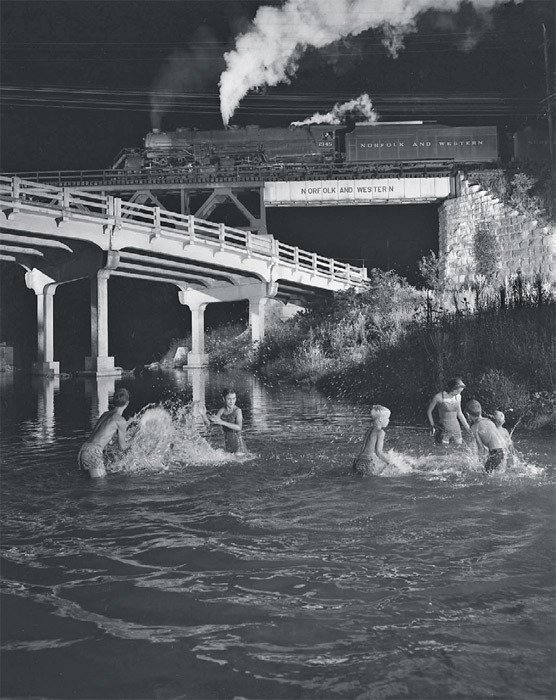

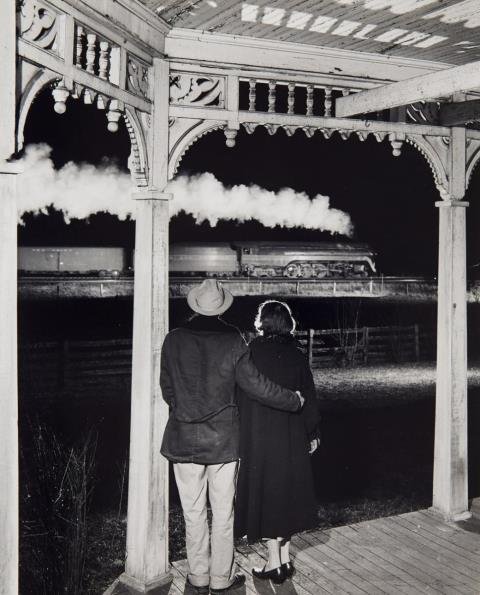

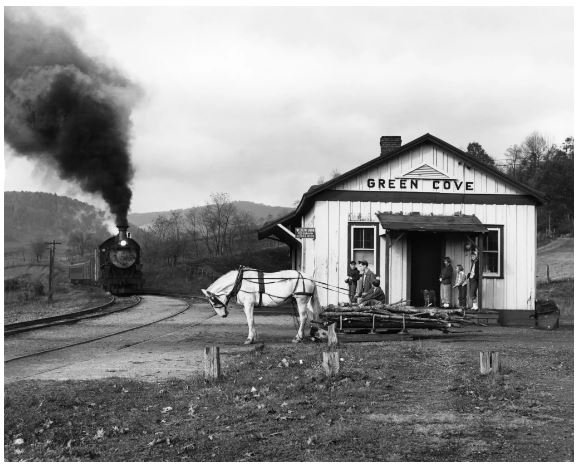

O. Winston Link is the King of Steam Train Photography. His mastery of the medium and artistry in creating night shots is unparalleled.

Link was incredibly prolific, taking more than 2,000 images and 100 7-inch reels of sound recordings in 21 trips to rural Virginia before the last of the Norfolk and Western steam trains were converted to diesel in the 1950s.

O. Winston Link and George Thom with Part of Equipment Used in making Night Scenes with Synchronizer Flash, March 16, 1956

Sotheby’s has sold many of these iconic shots, including Hot Shot Eastbound, Iaeger, West Virginia (1956), that features trains, planes, and automobiles occupying in the same frame.

But while he was obsessive over trains and lighting, Link left a lot of details to chance when it came to what his wife was up to. Unfortunately, his relationship with his wife, Conchita, grew strained once he suspected her of stealing prints and money from him in the early 2000s. Listen to the episode to find out more.

Conchita and O. Winston Link, from the documentary “The Photographer, His Wife, Her Lover.”

The O. Winston Link Museum collection in Roanoke Virginia, comprises the striking photographic and auditory works developed by photographer-artist O. Winston Link between 1955 and 1960.

Wishing that his legacy be preserved and remain available to the communities he traversed, Link began negotiations with Roanoke’s Historical Society of Western Virginia in 2000, personally selecting the site for the Museum, the former N&W Passenger Station.

In addition to photographs taken by Link between 1955 to 1960, the museum collection includes all of his photographic equipment and a reproduction of his dark room.

Episode 19: Carleton Watkins Detective

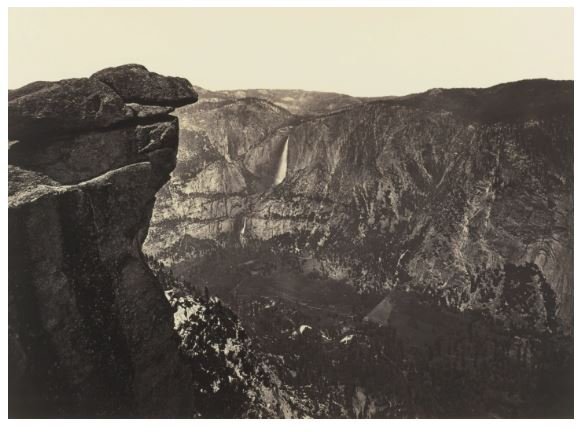

Cartleton Watkins is considered by many to be the foremost 19th century photographer of the American West. How do we rate Watkins prints when they come through the Sotheby’s Photographs department? How do we judge what is a “good” and “bad” print, and what are the metrics that we use to decide?

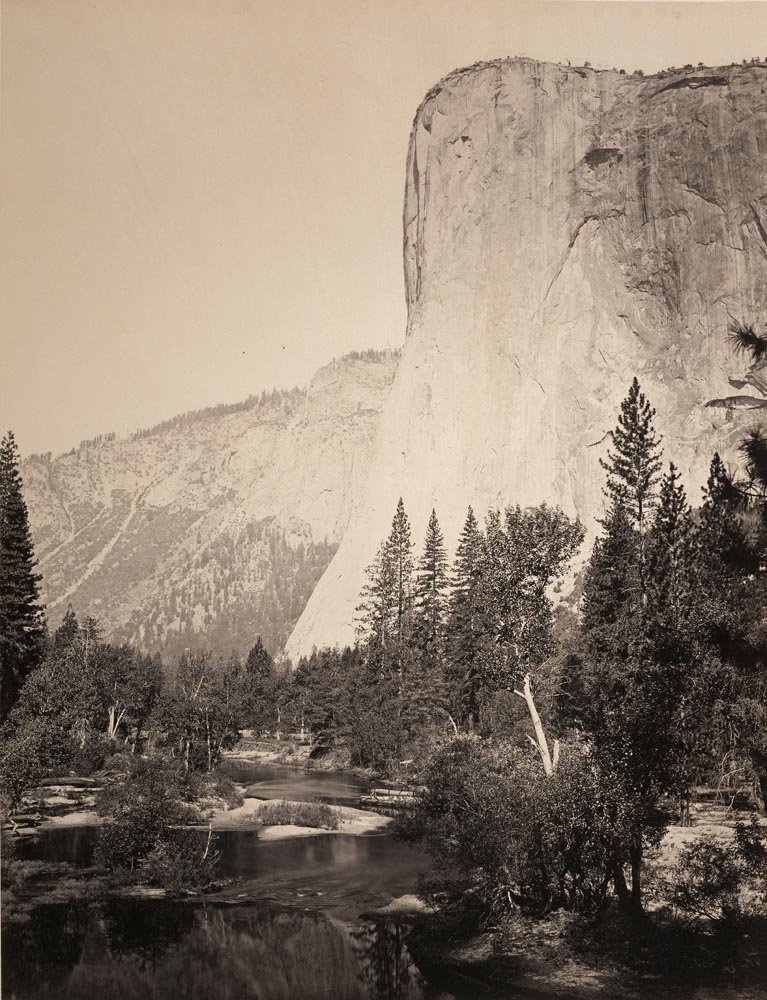

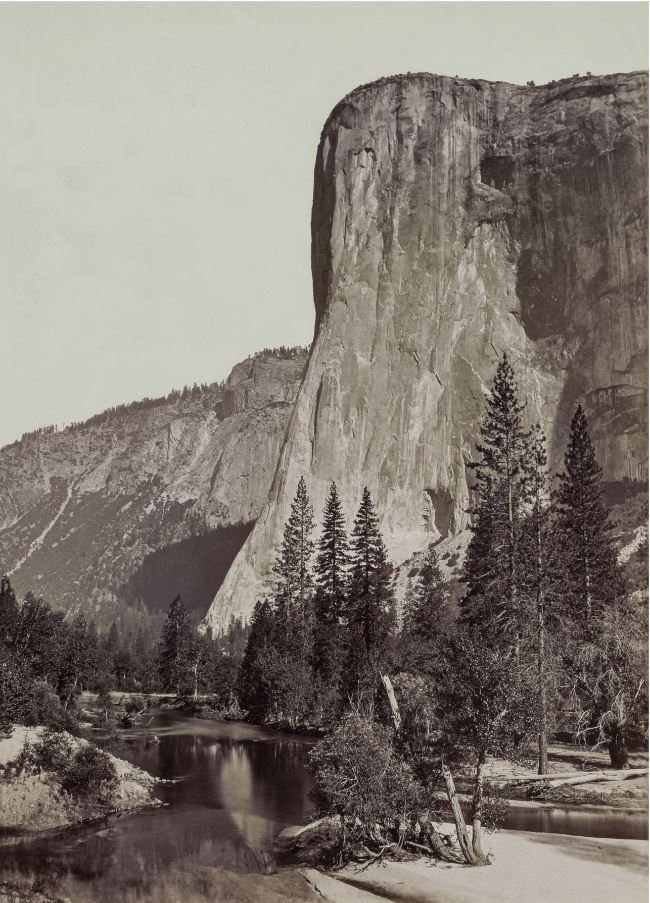

I consider technical skill, composition, and condition. Put all of those together and you have something like this incredible print that not only looks like it was made yesterday, but is a beautiful composition that keeps your eye moving throughout the landscape and has stunning detail.

Yosemite Falls (River View), 1861, Albumen print from wet-collodion negative, Private Collection, Montecito, California

When Carleton returned from his first trip to Yosemite in 1861, he had thirty mammoth plate photographs and one hundred stereoview negatives.

Stereo view of Cathedral Rocks, Yosemite

Becker Stereograph Viewer, patented 1866, The Art Museum, Princeton University, Gift of Henry-Russell Hitchcock

After his life’s work was lost to creditors, he set out to create his “New Series.” On the left is El Capitan from circa 1866, while on the right is the same subject 1878-81. This print sold at Sotheby’s for $17,640 in 2022.

Yosemite Falls from Glacier Point, 1878-81, sold at Sotheby’s, 2014 for $329,000

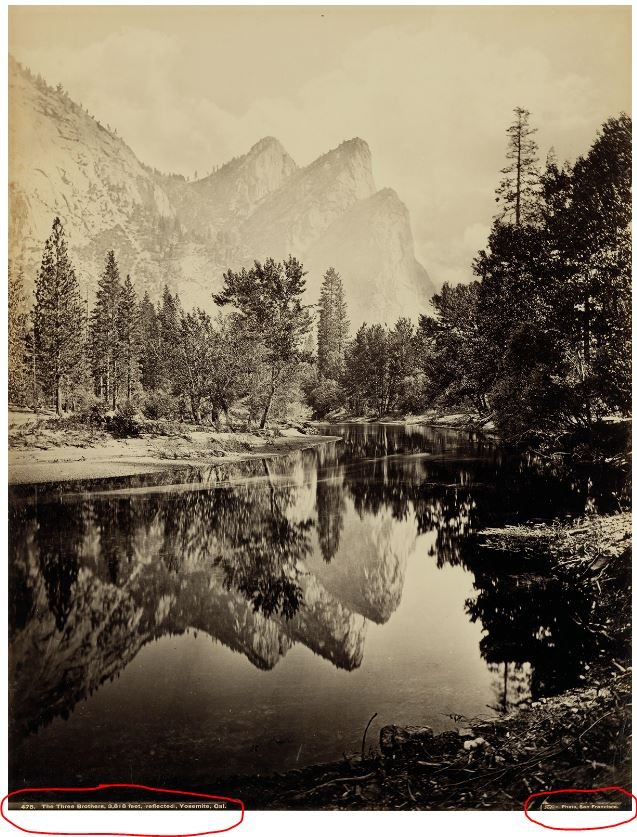

This print by Watkins, The Three Brothers, 3,818 feet, reflected, Yosemite, California, was printed by I.B. Taber. It sold for $2210 at Swann in 2020. You can see Taber’s credit, title, and number on the image:

I highly recommend visiting The Photographs of Carleton Watkins, a website with examples of Watkins prints, stereoviews, albums, and ephemera for more.

Carleton Watkins, Self Portrait, circa 1976

The sources I used for this episode were:

Peter Palmquist, Carlton E. Watkins: photographer of the American West (Albuquerque, 1983)

Peter Palmquist, “Carleton E. Watkins: Master of the “Grand View,” The Argonaut: Journal of theSan Francsco Historical Society, Volume 6, No. 2, Winter 1995-96

Winston Naef and Christine Hult-Lewis, Carleton Watkins: the Complete Mammoth Photographs (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011)

Tyler Green, Carlton Watkins: Making the West American (Oakland, 2018)

Episode 18: Margaret Bourke-White and the NBC Murals

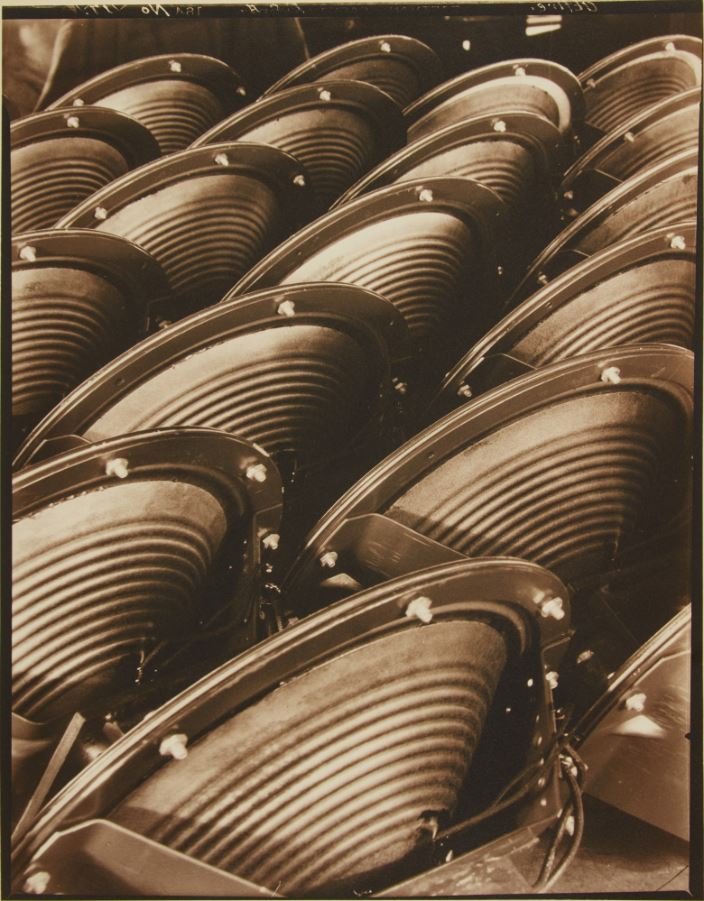

In October 2021 we sold a photograph by Margaret Bourke-White. It sold for a bargain- a little over $5000.

Radio Loudspeakers for NBC Mural at Rockefeller Center, 1933

It was a study of a portion of a photo-mural she completed for the NBC headquarters in 30 Rockefeller Plaza. The mural was 160 feet long and devoted to the subject of radio.

The lobby mural was unveiled in December of 1933.

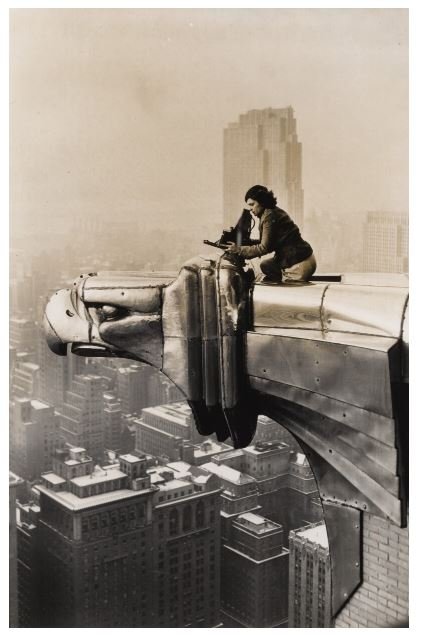

Margaret Bourke-White was only 29 when she completed this mural. She was independent, intelligent, charming, and skilled at her craft.

Oscar Graubner took this photograph of Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building outside her studio in 1933. We sold it at Sotheby’s for over $2000 in 2020 as part of our sale of Photographs from the Ginny Williams Collection.

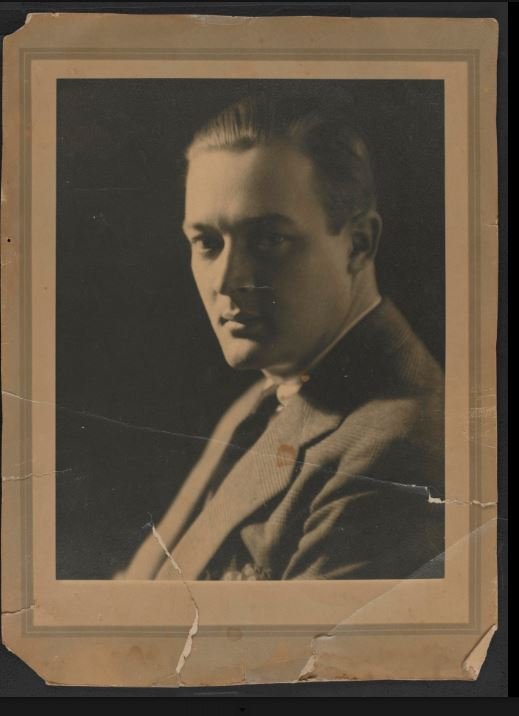

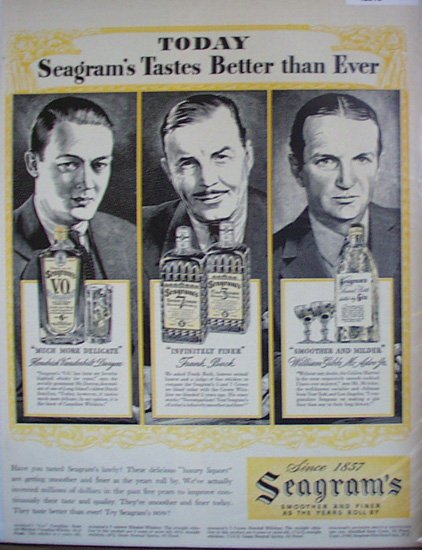

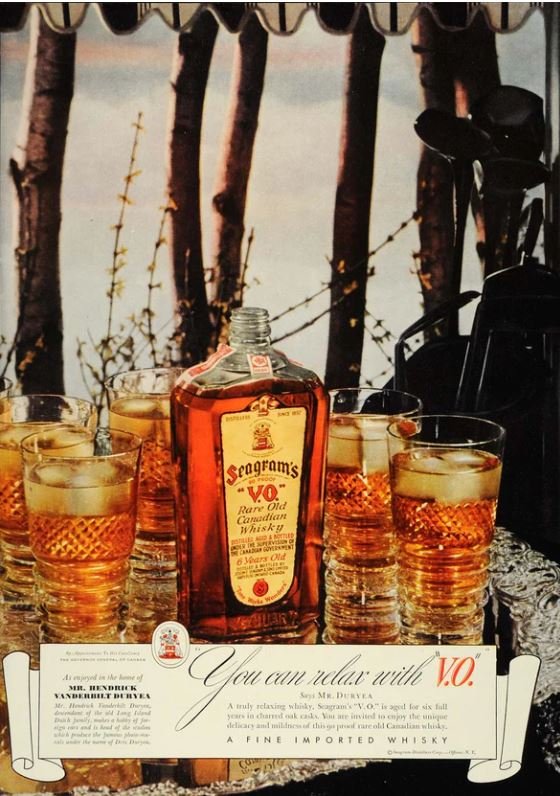

Drix Duryea was a wealthy commercial photographer hired to print and hang Bourke-White’s photographs for the NBC commission. Just like Bourke-White, he had his own endorsement deals like the athletes of today; he lent his name to Seagram’s Whisky.

The murals were removed in the 1950s but for over 15 years they were installed in the lobby of the NBC radio studios. Once television took over as the reigning medium, the murals lost their relevance. Today, this is where guests wait before entering Studio 6-B to see The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.

Episode 17: Second Chances

In this episode I introduced you to the famous yegg, hobo, professional criminal, and writer, Jack Black.

His book, You Can’t Win was published in 1926. It made him a bit of a celebrity. The American public relished his juicy tales of fencing goods, doing opium, riding the rails, and landing himself in jail a time or two or three.

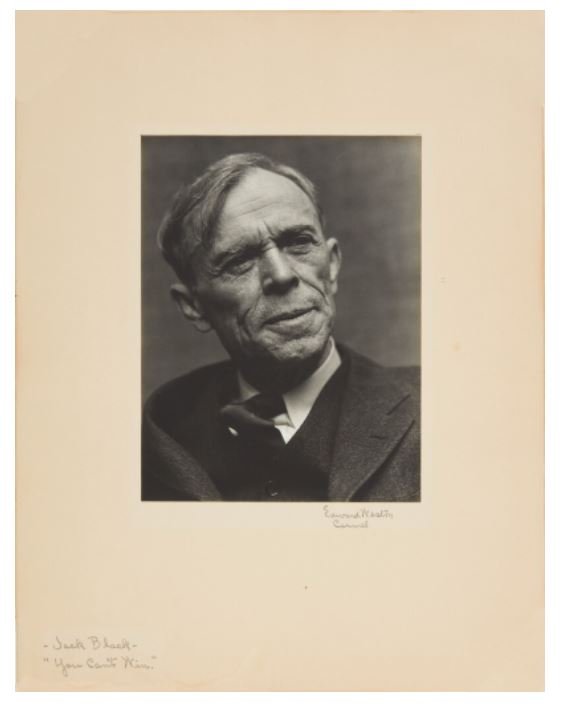

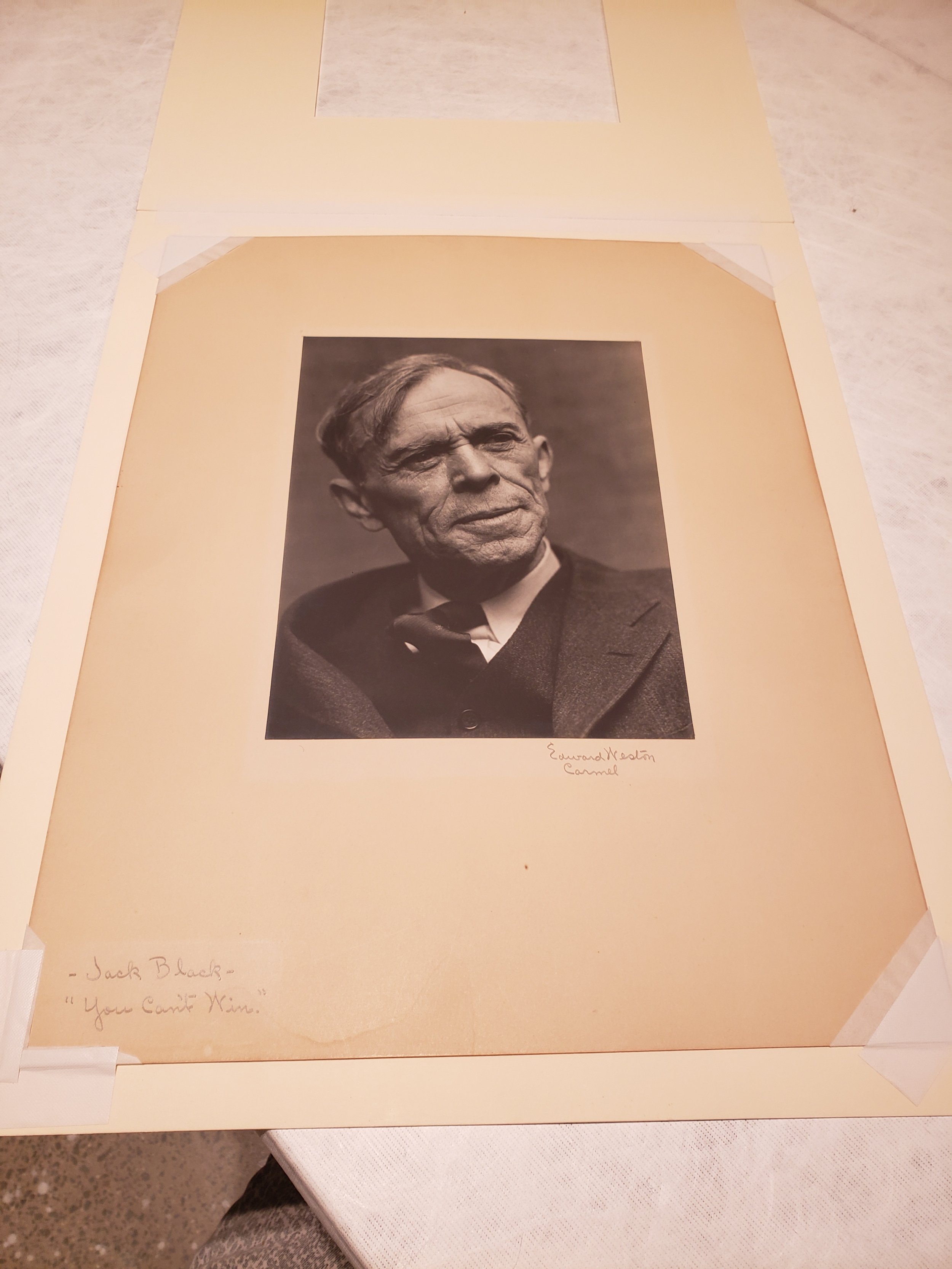

In 2020, Sotheby’s Photographs sold a portrait of Jack Black, taken in 1930 by Edward Weston. It shows Black looking aged from a hard life, but he smiles slightly, as if he’s just cracked a joke.

Jack Black by Edward Weston, gelatin silver print, mounted, signed, titled, dated, and annotated 'Carmel' in pencil on the mount, 1930, Sold at Sotheby’s New York, Photographs from the Ginny Williams Collection, 4 December 2020, $3,276. Here are some photographs I took while cataloguing.

“The right people are working on the wrong end of the problem. If they would give more attention to the high chair, they could soon put cobwebs on the electric chair. They lay too much stress on what the wrong people do, not on why they do it; on what they are, instead of how they got that way.”

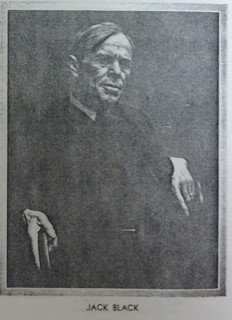

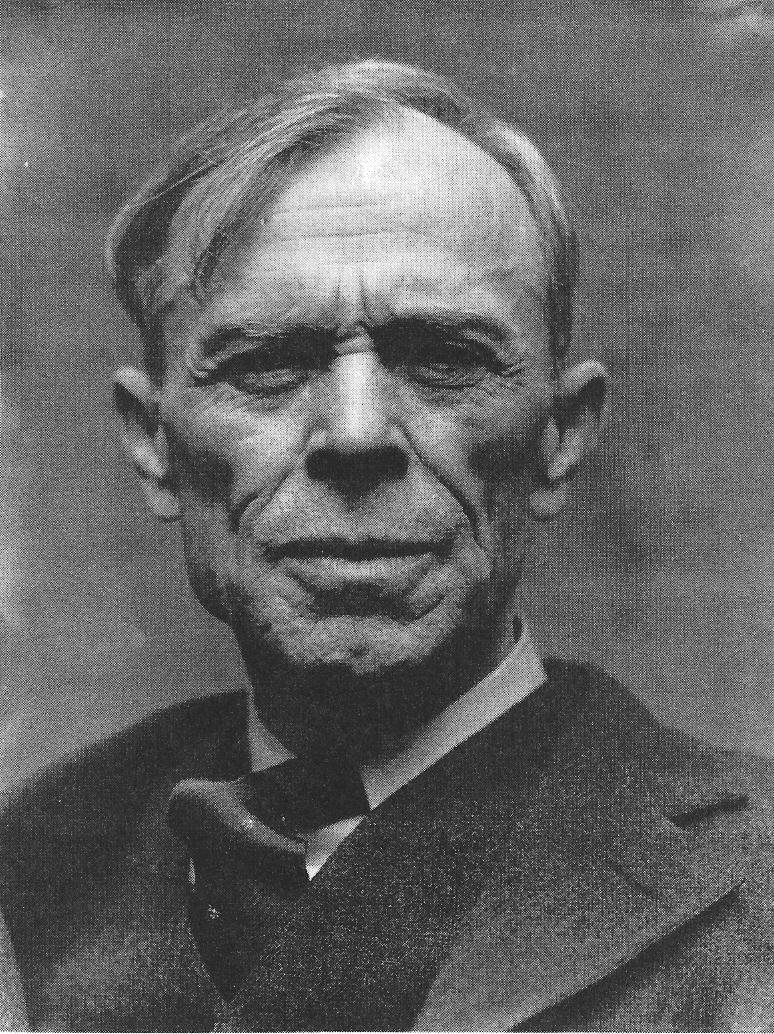

Two other poses (that we know of) were taken by Weston during this portrait session.

Left image was illustrated in: Rodriguez, José. “The Art of Edward Weston: Edward Weston—Crazy About Photography As Was Hokusai About Drawing.” California Arts & Architecture 38:5 (November 1930): 36–38. [Illus. p. 36 as: Jack Black]

Right image was illustrated in: Armitage, Merle, ed. The Art of Edward Weston. New York: E. Weyhe, 1932. [Illus. Plate 18 as: Jack Black---Burglar, Author (Not in Conger).]

(Thanks to Paula Freedman for this information!!)

It seems that artist Joe Coleman was inspired by Weston’s straightforward photograph of Black as the basis for the illustration he created for the reissue of the book in 2015.

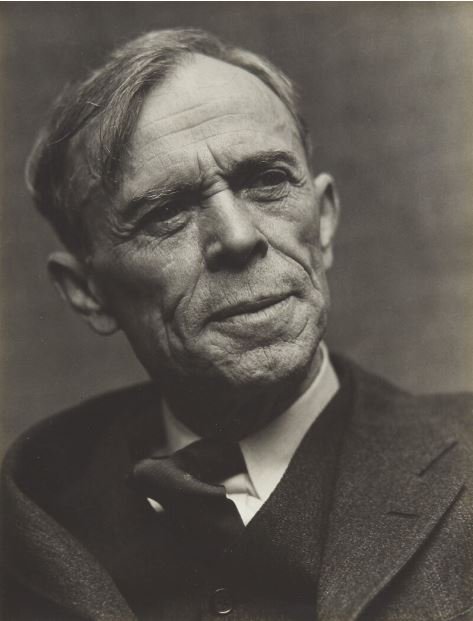

In this episode I also discuss photojournalism icon Lincoln Steffens, who was also photographed by Edward Weston in the early 1930s. The portrait below is in the National Gallery.

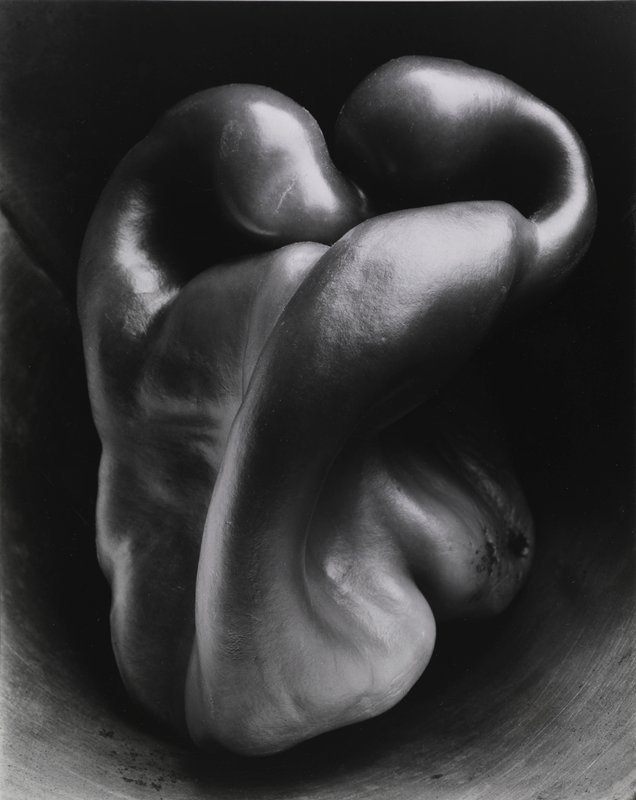

Another person discussed in this episode making waves in 1930 was Edward Weston. That year, Edward Weston took a series of still lifes of a some simple garden peppers. One of those images, of a pepper he placed inside a funnel, or Pepper Number 30, has become an icon of photography. The negatives from that summer would change the way he approached his work for the rest of his life.

Edward Weston, Pepper No. 30, 1930

Next up: The amazing Ginny Williams.

Sotheby's was honored to offer over 450 works from the celebrated collection of Ginny Williams across a series of sales throughout 2020. The photographs from Ginny’s collection included everything from Dorothea Lange to Sandy Skoglund! Ginny was quite simply a legend. Born in rural Virginia in 1927, Ginny moved to Denver, Colorado in the late 1950s with her husband, Carl Williams. An avid photographer herself, who studied with Austrian-American photojournalist and photographer Ernst Haas, her collecting journey began with classical figurative photography. Her passion and keen eye eventually prompted her to open her namesake gallery in Denver in the 1980s. While her passion for photography never waned, remaining a primary focus of both her gallery and private collection, her voracious curiosity quickly widened her curatorial focus. Over time, Ginny became increasingly courageous and experimental in her selections, venturing into Abstract Expressionism and Contemporary Art and following her artists themselves through gallery shows and museum exhibitions. As the years passed, Ginny became as much of a trailblazer as the artists she collected.

Ginny Williams

In closing, I’ll copy in full one of Jack Black’s article titled “What’s Wrong With the Right People.” It appeared in Harper's Monthly Magazine, June 1929.

The author of this article was for twenty-five years a criminal and served several prison terms; what he says about the criminal’s state of mind and the effect on him of society’s present method of combating crime is, therefore based upon direct personal knowledge.—The Editors.

“There’s a lot of law at the end of a rope.” That was the gospel of the California Vigilantes when they set out to clean up the crime wave of ‘Forty-nine. In the name of law and order they were going to take a short cut, kill a few killers and horse thieves, and make San Francisco safe for business. They were the “right” people of their time, noble gentlemen upon a noble mission bent; but like noble gentlemen turned reformers, all down the ages, they got drunk on blood-power. As long as they kept the rope for horse thieves the populace looked the other way, but when they succumbed to the inevitable temptation to hang business rivals and political enemies, this same populace made short shrift of them.

That was a world of ox carts and covered wagons. Ours is a world of automobiles and airplanes. Most things have moved along, but eighty years has made little difference in the methods with which the right people deal with the “wrong” ones. In the main they are facing the crime wave of 1929 with the mental attitude of the Vigilante.

“There’s enough law at the end of a night-stick.” This has the Vigilante ring to it, but it was spoken by New York’s most recent police commissioner at the outset of the clean-up campaign with which he began his regime. The only result apparent so far is a lot of indiscriminate clubbing and shooting by the police and a corresponding increase in murders and crimes of violence.

These are violent days. We are all agreed on that. The question is, who is responsible? Are the wrong people making the right people violent or are the right people making the wrong people violent? Or is it fifty-fifty?

From my seat on the side-lines it looks as though society were trying to out-gang the gangster, out-slug the slugger, and out-shoot the shooter, without pausing to ask whether it won’t result in simply pyramiding violence.

The right people all over America in press and pulpit are writing and preaching about the wrong ones. Crime commissions and individuals high and low, from the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to the smallest small-town reformer, are surveying and recommending, and resolving and whereas-ing them. Legislators are legislating, and the police are pistoling and night-sticking. All are preaching and practicing more violence as a cure for crime.

Is there any justification anywhere, in any time, for believing this method will work? I don’t find it. I do not pose as an authority on crime and criminals. My testimony is that of a bystander — a guilty bystander, if you like, for I have survived four penitentiaries and numerous county jails….What happened to me as an individual is unimportant. I am useful only as an exhibit in the case; but if the laws which the right people are making to-day had been in effect fifteen years ago, I should never have had a chance to stop stealing and learn working. I should probably have been stopped by the rope, the chair, or a policeman’s bullet. Had I escaped these I should be a life-timer in some such prison as Dannemora or Charlestown, spitting my lungs out against a whitewashed wall and, like other life-timers, preaching to young offenders the doctrine of “shoot, and shoot first.”

Besides being wrong myself, I have known intimately, in and out of prison, almost five thousand wrong ones. This may seem a wide acquaintance, but in jail one has ample time for social intercourse. These five thousand constitute a cross-section of the underworld from which the crime wave bubbles up. They ranged from the petty thief who “snares” a door-mat with “Welcome” on it, to that prison patrician, the bank burglar. The door-mat thief was just as interesting to me as the bank burglar. It wasn’t what they did that interested me but why they did it. Some were mental cases, pathological, with bow-legged minds: in prison parlance, “a kink in the noodle.” Some were in prison because they had too little money and some because they had too much. Some because of ignorance and some because of over-education. Some were there because they were sent into overcrowded professions, when they should have had trades. Booze, “hop,” jealousy, avarice; all furnished their quota. A few appeared to be there from perversity — just downright cussedness.

The majority were guilty as charged, or of kindred offenses, though here and there one was innocent. Except for those convicted of crimes of passion, none had leaped into a criminal career overnight. Most had arrived by slow and gradual stages, the result of action and reaction. One was there because of a boyhood feud with the neighborhood cop. One because he lost his job in a strike. One because his wife got sick and his children were hungry.

We’ll assume that most of them were the initial offenders. They wronged society, and society, not understanding, wronged them back — with interest. The vicious circle that leads from one penitentiary to another had begun. All their stories could be hooked together on one thread: hatred of the police, contempt of the law, and fear and mistrust of the whole legal machine.

ii

My own case is typical. Up to the age of fifteen I thought a policeman was a hero, a person to be looked up to and trusted and confided in. Then one evening I was mistakenly “picked up, taken down, and thrown in” by one of them. The treatment I got in the jail from him and his brother officers shot that illusion all to pieces.

Every subsequent contact for twenty-five years strengthened those impressions, and it has taken me the best part of a lifetime to learn that the cop is a victim of the same machine which makes the criminal.

I got my first lesson in violence that first night in the jail. For twenty-five years I punished and was punished. I hunted because I was hunted. I showed no consideration for anybody because I expected to receive none. I learned the game of violence thoroughly, from the police, the courts, the prisons. In the end I came to believe that I could survive only by using violence-and using it first.

I know hundreds of reformed criminals and I don’t know one who was reformed by a policeman’s night-stick, a severe sentence, or prison cruelty. A brutal flogging in a Canadian prison, and, years after, three days in the murderous strait-jacket on a dungeon floor in California, certainly did nothing to turn my thoughts toward reformation.

The strait-jacket was to the prison warden what his rope was to the Vigilante, what the New York Commissioner would make of the night-stick — a short cut. The jacket had a brief reign and a swift and violent end. So far as I know, every man who was subjected to its ferocious punishment was so hopelessly maimed that he was a derelict for life, or so twisted mentally that he became a homicidal maniac. They left the prison like the little Jewish tailor whose hands were too shriveled to do any honest thing except to catch pennies on the street corner, or like me, poisonous and revengeful. This attempt to maintain order by “throwing the fear of God into them” failed as all such systems fail. It culminated in the bloodiest prison break in the history of the United States. Of the twelve men who escaped, six of the most desperate are still at large, with ropes around their necks, and the murders they have committed to keep out of the hangman’s grasp are almost unbelievable.

When I left prison, still weak from the effects of the strait-jacket, I swore to myself that from that time on I would be a creature of the night. I vowed I’d never let the sun shine on me, never make another friend or do another kindly act. The prison officials were safe in their prison, and I turned on society for my revenge. Within three months I was back in jail charged with robbery and shooting a citizen who refused to be “stuck up.” If he hadn’t had a good doctor and a good constitution, I shouldn’t have lived to discover that the pen is mightier than the jimmy or the six-shooter. If the Baumes Law had been in effect, I should never have discovered it, for that law robs the judge of all discretion. On the fourth conviction it is mandatory upon the judge to sentence a defendant to life imprisonment, whether he shoots a citizen or steals a pair of shoes.

For the past fifteen years I have been feeding and clothing myself instead of letting the tax-payers do it, because, at the time of my life when I least deserved it, I met trust and judicial leniency, which gave me hope. The judge who sentenced me to a year when he might have locked me up for life and thrown the key away, took a greater chance on me than I ever took on anything. He stopped my stealing as effectively as a hangman’s rope. He gave me my life and I couldn’t doublecross him any more than I could doublecross the friend who once cut the bars in a jail window and gave me my liberty. Loyalty is the only virtue of the underworld, and the judge appealed to that. He put me in a hole where I had to stop stealing and fall into the lock-step of society.

I repeat that I have never known one criminal who was reformed through cruelty. Such reformation as I have achieved is due, initially, to the act of the judge who said, when he sentenced me to a year instead of to life:

“I believe you have sufficient character to build a new life. I will give you that chance.”

iii

The records are full of the cases of men, notorious for their violence, who reformed when their loyalty was challenged. It’s the petty criminal, the weak man, without character enough to be very good or very bad, who violates parole, or any sort of confidence. He doublecrosses his fellow crooks and he doublecrosses society. The “worst” man is often the best bet. Frank James, train-robber and killer, threw away his guns when the governor of Missouri pardoned him. Al Jennings now pushes a pen instead of a six-shooter, thanks to Roosevelt’s pardon. Emmett Dalton, Chris Evans, Jack Brady, Kid Thompson — all highwaymen and killers — lived out the letter and spirit of their paroles.

“Desperate men bereft of hope are potentially violent men. ”

Desperate men bereft of hope are potentially violent men. The Baumes and kindred laws which destroy hope are violent laws, and they breed violence. At best they amount to nothing more than a policeman’s order to “move on.” At the worst they create a blind alley from which the only exit the desperate criminal knows is “Drop him before he drops you.” The result — a dead policeman here, a dead citizen there, a dead stool pigeen somewhere else.

Wrong ones and right ones are much alike when their backs are to the wall. They are both apt to get panicky and spoil what might be a polished, professional piece of work. A pickpocket with his hooks on a thousand-dollar poke may fumble it. There’s too much at stake. The crime-doctors, faced with an appalling increase of crime, are crowded into hasty action by a lot of nervous citizens who want the crime-wave stopped overnight. They recommend more laws, when they already have more than they can enforce. They recommend more punishment, when the experience of all the ages has shown its futility. They listen to the hue and cry against “mollycoddling” criminals, and restrict parole, probation, and pardon — the only measures that permit a criminal to reform. To lighten a leaky boat they throw overboard the biscuits and water.

Governor Clifford Walker of Georgia lifts a calm voice in the clamor for revenge: “The extreme crime-wave reformer,” says the Governor, “would abolish parole, probation, and indeterminate sentence, increase the severity and length of punishment, and frighten human nature into submission….Crime cannot be prevented by fear of punishment, or by harsh, cruel, or inhuman treatment. Such methods have been given a fair trial. There is no crosscut to the transformation of the delinquent.”

The federal probation officer of Pittsburgh, reporting to the National Probation Association, quotes some telling figures. He says that probation work on 106 offenders cost $1,097. The same offenders, had they been sent to prisons or reformatories, would have cost $26,452. Probation work, then, brought about a net saving of $25,355 to the government.

If from eighty to ninety per cent of the prisoners respect parole and probation, as the statistics show, it is a paying proposition, and any attempt of the right people to abolish or diminish it is bad business. If parole and probation were abolished entirely, probably seventy-five per cent of the prisoners would serve their sentences and come out of prison to return to their criminal careers.

Too much of the attention of the right people is focused on the habitual criminal. If every habitual criminal, in and out of prison, were poisoned or pardoned tomorrow at sunrise, we should still have a crime-wave, because the right people’s system of dealing with young offenders is guaranteed to grind out professionals.

“Society should pay more attention to the reform school than to the penitentiary. The character of the policeman who gets the boy first is more important than the judgment of the judge who gets him last. By the time the young offender faces a judge of the criminal court he is a finished product. Society’s best chance to turn him away from crime is before he has hardened into a professional. Therefore, the juvenile court is more important than the higher courts, and more common sense in the police courts would mean less congestion in the court of criminal appeals.”

iv

Recently a country boy appeared in the dock of a New York police court charged with vagrancy. He told the judge that he had a job and asked to be released. The judge was doubtful.

“When did you get the job? Since you’ve been arrested?”

“Yes,” the boy replied. “The policeman who arrested me got it for me last night.”

The judge complimented the policeman at great length; a reporter present saw a “story” in what had happened, and his editor printed it — because it was news. What would happen if it weren’t news, if all policemen acted that way? In Los Angeles a rosy-cheeked, redheaded, boyish young person of seventeen was picked up by a policeman for annoying girls on the street. At the station it was discovered that the young person was a girl in boy’s clothes. Police and press jumped to the first obvious conclusion, that she was a very abnormal person, and treated her as such.

But the juvenile court of Los Angeles, where Dr. Miriam Van Waters, the psychologist, is referee, is a very intelligent institution. There it developed that instead of being abnormal, the girl was extremely normal. She was a masculine type; she played boys’ games and lived the boy’s life. When she arrived at the stage where she wanted the normal girl’s share of masculine attention, wanted to be a sweetheart instead of a playmate, she found she had none of the wiles of her sex. She was torn between fear of being unable to attract boys and fear of not knowing how to act if she should attract one. She had no girl friends to advise her, so she put on boys’ clothes and went out to flirt with girls to find out how they behaved with boys. Her approach must have been clumsy or she would not have been arrested. If the approach of the juvenile court had been equally clumsy she would have gone into an institution — en route to heaven knows what. Instead, she got some sound feminine advice about clothes and conduct to restore her ego and give her confidence in herself.

If more of these bent twigs were approached in this scientific attitude, wouldn’t there be less dead wood lying around the prisons? Wouldn’t there be more respect for law and law-enforcers? Disrespect for the law in this country is not confined to the criminal, either juvenile or habitual; and the best minds in the country are trying to explain it. Is it, perhaps, because the law does not respect the people?

In England crime is less of a problem. The fact that with a homogeneous people there is no racial friction only partly accounts for the small percentage of criminals. The principal reason is that the Englishman respects the law because the law respects him.

Only recently England has been aroused from end to end over the arrest of a girl in a London park, without sufficient evidence of misconduct. Englishmen rose up from their breakfast tables when they read what had happened, and cried out, “That might have been my daughter. It’s outrageous.” They wrote letters to the Times about it; and the police of England are pretty responsive to such protests.

All crooks are equal under the law in England. The offender is not slobbered over by a lot of sentimentalists but neither is he clubbed into a “confession” by the police. There police protection means protection of the Englishman. What is “police protection” coming to mean here?

The police–crook alliance in this country discourages decent people and develops all the latent larceny in the rest of us. Those on the borderline of criminality are encouraged to take a chance; they make a plunge for easy money in the hope of becoming one of the many favored and protected aristocrats of the underworld; and the high-school boy, reading newspaper reports of the gangster’s heroic death and magnificent funeral, forgets his Lindbergh and says to himself, “Not so bad.”

The right people are all for bigger police forces. The crime commission’s reports bristle with phrases like “lengthening the arm of the law” and “strengthening the police arm.” I will go them one better. I am for bigger and better police forces. A bigger police force with the same system would only multiply the evils which the right people are trying to correct.

The case of X is an instance of the sort of police work which is guaranteed to fix in the mind of an individual a lasting hatred of the police. X was a young girl of a type common on the fringes of the underworld. She was attractive, soft, and used to the luxurious living provided by patrons of the night-clubs. Her lover was in jail charged with a series of robberies. The case against him was weak. The girl was arrested on the theory that she might have information which would aid the police in convicting him. She denied all knowledge of the crime. The detective who made the arrest ordered her locked up and said to reporters in the press room, “Don’t worry. She’ll come through. I’ve got her locked in the dirtiest cell in the city prison. She won’t get a bath — she won’t wash her face for three days. She’ll get good and lousy, and then she’ll squawk.”

He was right, and the information he got sent the man she loved to prison. Already a social outcast, she went back to face the contempt of the underworld, too, for she had committed the only unpardonable crime. She lives in an atmosphere of hatred and scorn, shadowed by the fear that any night she may be “taken for a ride.”

The case of X is a straw in the wind and what happened to her and her lover is of little consequence. But the detective’s action is a perfect example of the sort of police work which breeds more crime. For while his ingenious plan brought about a quick conviction, it might well have caused the girl’s murder, and that murder, another hanging. Who can estimate the results of a lifetime of such detective work, where every act radiates hatred, fear, and mistrust?

By a better police force I mean a police force composed of men who have a less punitive and a more scientific attitude toward crime and criminals. Such men are not to be had for the wages paid by most municipalities. The Philadelphia police scandal shows that the men are paid salaries which are almost an invitation to graft. Suggest raising their salaries and the average voter would say, “They’re getting theirs now. They’re getting fat.” But what legitimate inducement is there for ambitious young men to go into the police department? Handicapped by poor pay, ridden by politicians, and surrounded by an atmosphere of graft, with little promotion except through favoritism, what chance is there for good men to do intelligent, humane, and constructive police work?

The same conditions exist in the prisons. The guards are scandalously underpaid, and most of them are broken down, rejected ward heelers. The captains and lieutenants are usually small politicians on the shelf, while the warden is too often a graduate of the guard-line. If by any chance a business man or a humanitarian is chosen as warden of one of our prisons, the politicians immediately sharpen their axes for him, and off goes his head with the first swing of the political pendulum. The fate of the late Thomas Mott Osborne who revolutionized Sing Sing and was put out by the politicians, a broken and discouraged man, proves this, as does the recent removal of Warden Smith of San Quentin, California.

August Vollmer, nationally known as a scientific chief of police, gets amazing results in his handling of criminals in Berkeley, California, where he is not hampered by politics. Called to Los Angeles to reorganize the police department, he lasted just one year. Hamstrung by politicians and doublecrossed by his subordinates, he gave it up as a job too big for anyone man. Vollmer wouldn’t “play along” with crooks-in-office, and it was not until he had shaken the dirt of Los Angeles County from his feet that the district attorney who balked him at every turn was convicted of taking bribes and sentenced to San Quentin.

v

The problem seems too big for any one crime commission, or any number of crime commissions for that matter. But if anyone thing seems certain, it is the folly of more laws and more punishment.

Lao Tse, who was a contemporary of Confucius, said, “Govern a kingdom as you would cook a small fish,” meaning do not overdo it. “The more active is legislation, the more do thieves and robbers increase.”

A great Chinese Emperor, founder of the Ming Dynasty in 1868, took his cue for abolishing the death penalty from this philosopher. “Almost every morning ten men were executed in public,” wrote the Emperor. “By the same evening a hundred had committed the same crime. Lao Tse said, ‘If the people do not fear death how then can you frighten them by death?’ I ceased to inflict capital punishment. I imprisoned the guilty and imposed fines. In less than a year my heart was comforted.”

England made the same discovery. They didn’t stop hanging people in England for sheep-stealing, shop-lifting, or pocket-picking because it stamped out those crimes. They stopped because of the alarming increase in the murder rate. The law made potential murderers out of petty thieves. The extreme penalty failed to stop pocket-picking even in the shadow of the gallows. Men were arrested for picking the pockets of a crowd assembled to witness the hanging of a pickpocket. Once the English hanged people for sixty different offenses. Now they are considering the abolition of the death penalty, even for the only remaining one. England has proved that violence doesn’t cure violence.

It is safe to say that if every voter in America could be forced to witness a hanging or an electrocution, capital punishment would be abolished at the next election. Certainly no one who has lived through one of those black Fridays in prison, could doubt that evil walks with the hangman. As the day of execution draws near the prison becomes a smoldering volcano. The convicts grow sullen and short-tempered. Old grudges are opened, old hates revived. Stool pigeons are stealthily slugged; guards are cursed, defied, and assaulted. The dungeons are filled with unruly prisoners “boiling up” with hatred. On those Fridays I have seen the most murderous knife-duels between prison enemies. In the stone quarries at Folsom men threw thousands of dollars’ worth of valuable steel tools in the canals and smashed with sledge hammers pieces of carved and polished granite upon which they had worked for months. In a blind, helpless surge of revolt they destroyed whatever they could get their hands on. In the “diner” I have seen hungry men hurl their food to the floor, refusing to eat “the damned hangman’s stew.” On this day of legal violence imprisoned men became so violent that the wardens finally hit upon the plan of keeping the “main line” locked up until after the execution. Now men sit in their cells brooding in silence, or make the prison corridors ring with their hoots and curses.

Of one thing the right people may be sure: no prisoner’s thoughts are turned toward anything of good on such a day.

vi

“What, in a nutshell, is my case against the right people? I contend that more laws and more punishment will mean nothing but more crime and more violence. ”

What we need is more science. We need more emphasis on prevention than on punishment. More attention should be paid to the juvenile from the broken home and from the overcrowded and unsanitary slums. Scientists, school teachers, and social workers who are trying conscientiously to fit the delinquent for the job of living, should be freed from interference by politicians and job-holders whose methods have already been tried and have failed. Perhaps there should be more vocational guidance directing the youth into undermanned trades instead of overcrowded professions.

Any intensive study of the population of any American prison will show that most of them are men who have not been trained for the job of living or making a living. During my time at San Quentin a notice was tacked on the bulletin board asking for ten accountants to apply at the Captain’s office to help on the annual reports. When the day came forty prisoners applied for the work, and all of them were qualified to do it. There were college men in San Quentin, lawyers, doctors, dentists, bookkeepers, accountants, mathematical experts, inventors, writers, lecturers, and one poet. Later in the winter when a brick factory chimney was damaged by storm, a bulletin was posted calling for bricklayers. None appeared, although the job carried privileges including “three squares a day” and possible parole if it were well done. A search of the register disclosed several “bricklayers,” but on inquiry it developed that they were just plain crooks who had “thought it looked better to give some kind of a trade.” The best the Captain could find was a man who had once served as bricklayer’s apprentice. It took him three months to mend the big chimney, and he ate his three meals a day in the guards’ quarters and got an immediate recommendation for parole.

Doesn’t that show that the skilled artisan is not the man who does the going to jail?

If the crime commissions would utilize the best laboratory material they have — the criminal — the reports they submit would be more valuable. Their conclusions and recommendations are the result of a long-distance, ex-parte diagnosis. It is as though a committee of doctors solemnly meeting in Boston or Washington were to diagnose the cases of ten thousand patients scattered all over the United States, without ever examining one of them. Imagine these same medical men solemnly writing one formula to cure them all. Yet ridiculous as this may seem, it is more reasonable than a blanket recommendation for the cure of crime, without examination, or autopsy, for the causes of crime are more varied than the causes of disease.

The secret of the cure of crime — if there is one — is contained in a knowledge of its causes. The psychologist, with his cool scientific mind and a background of knowledge secured through experiment and observation, is only just beginning to learn why we behave like human beings. How much more difficult is it to determine why so many of us behave inhumanly! Yet without so determining, who can prevent the crime wave of to-morrow which is in the kindergarten of to-day?

The right people are working on the wrong end of the problem. If they would give more attention to the high chair, they could soon put cobwebs on the electric chair. They lay too much stress on what the wrong people do, not on why they do it; on what they are, instead of how they got that way.

Danny Ryan’s mother said it all when she held out her arms to her son in the cell next to mine and cried:

“Danny, boy, how come you so?”

.

Further reading:

"Out of prison", San Francisco Bulletin, February/March 1917.

"The big break at Folsom", San Francisco Bulletin, January 1917.

Black, Jack "What's wrong with the right people?", Harper's Monthly Magazine, June 1929.

Black, Jack "A burglar looks at laws and codes", Harper's Monthly Magazine, February 1930.

"Jack Black's Tales of Jail Birds", New York World, December 21, 1930.

Jamboree, with Jack Black and Bessie Beatty; Elizabeth Miele, producer, 1932.

Episode 16: Lost and Found Dept.: The One-Man Historical Society

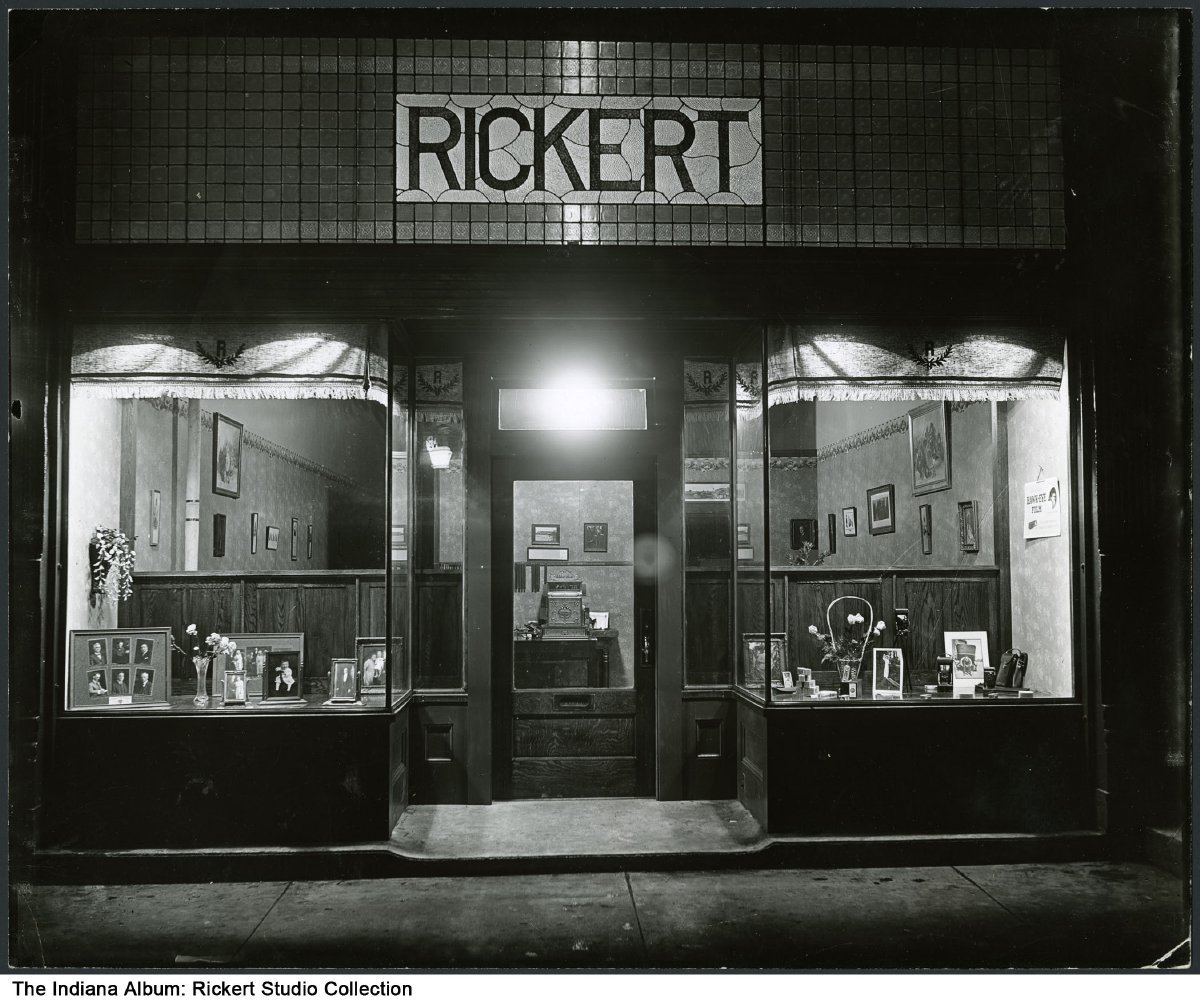

In the early 2000s Alan Pflieger, a photographer in Huntington, Indiana (and my dad), acquired a huge archive of negatives from the Rickert Studio, which had been in operation from 1912 to 1986. He saved the negatives from being destroyed. My parents stored these negatives in their house for years until, through a funny series of events, they ended up making their way to the Huntington County Historical Society.

William Rickert’s studio, Huntington, Indiana, circa 1925

Through the years that he had them in the garage, people would call Alan and ask for photographs of their family members who had been photographed at the studio, and he would make prints for them if he could find the negatives in the vast folders in storage.

Studio employee working in the Rickert Studio darkroom, circa 1925

A photographer in his own right, my dad knew the importance of preserving these negatives, not only for the families of the sitters, but also because they told an important story of Huntington County through the years.

William Rickert Studio, Huntington, Indiana, circa 1915

A salesperson in the Rickert Studio store, 1913-39.

The Rickert family, Huntington, Indiana, circa 1925. Left to right: William F. Rickert (1886-1976), Letha Marie, Robert L., Glenn Edward, and Ella (Henline) Rickert (1886-1969).

Colleen Pflieger (my mom), circa 1950, photograph by the Rickert Studio.

Colleen and Alan Pflieger on their wedding day, 1970. Photograph by Rickert (taken at Trinity United Methodist Church, Huntington, Indiana)

The Abbott Family, photograph by the Rickert Studio

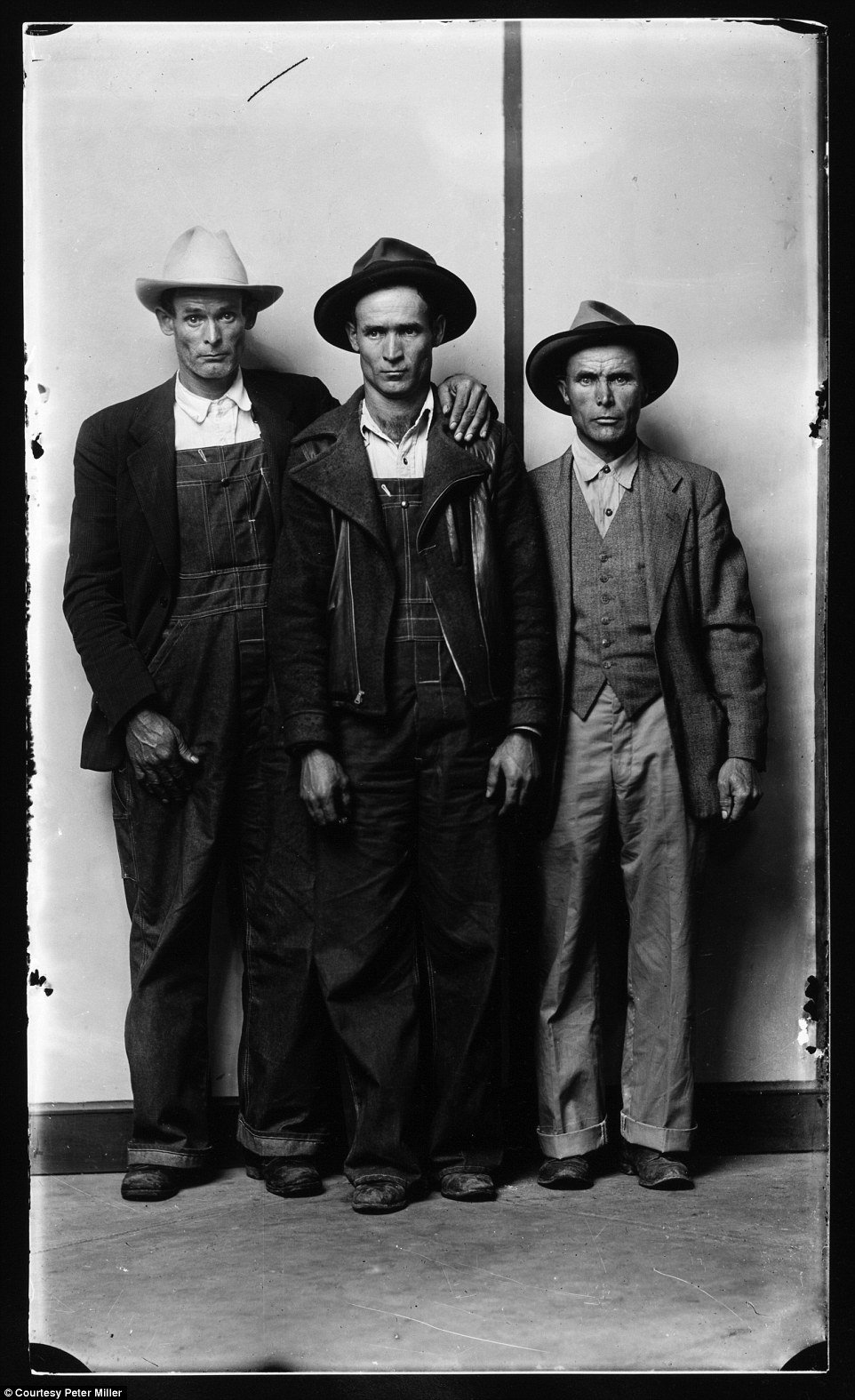

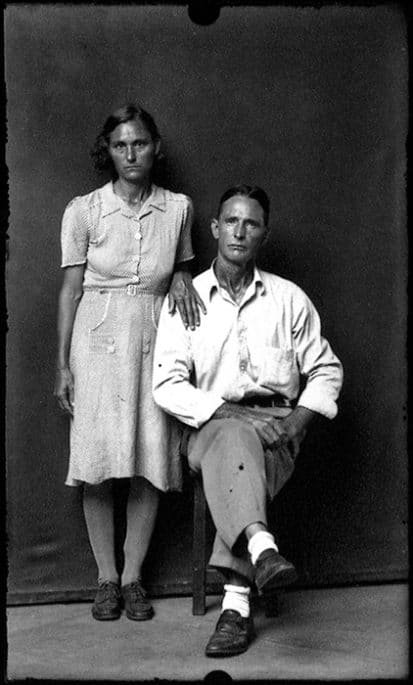

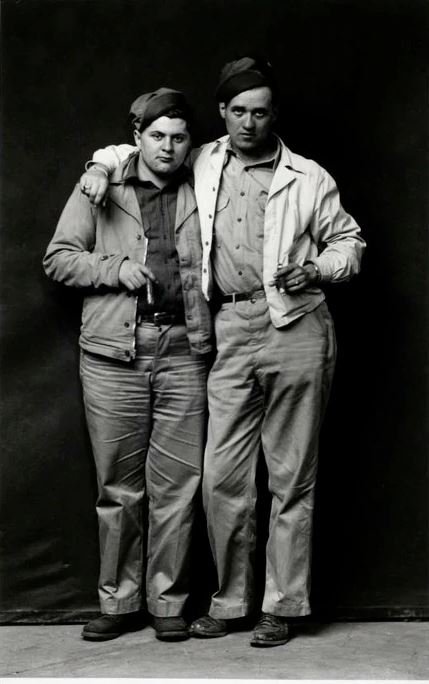

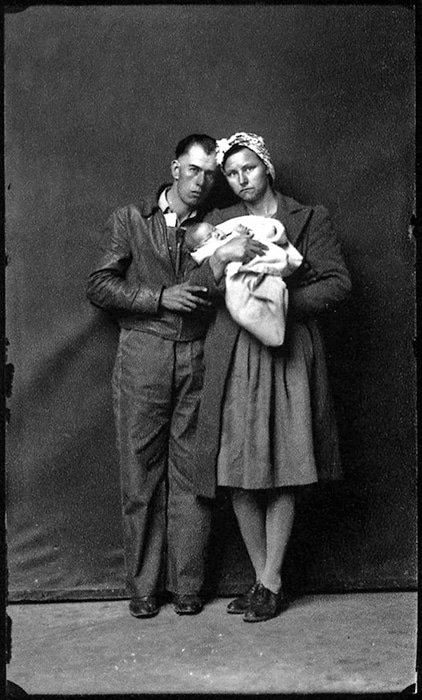

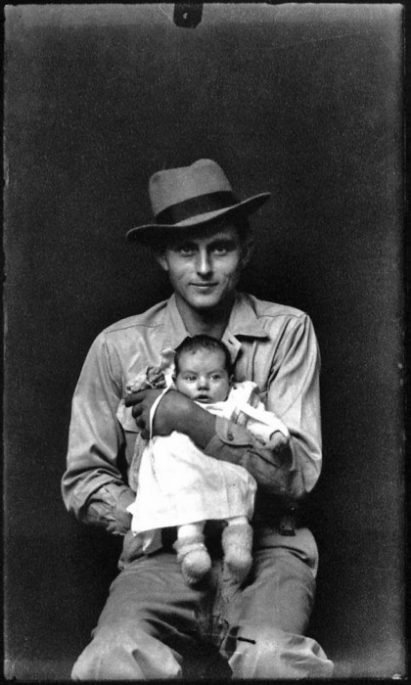

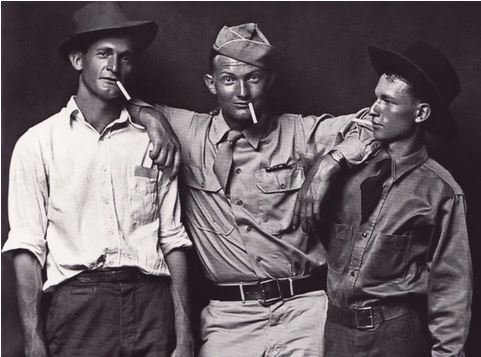

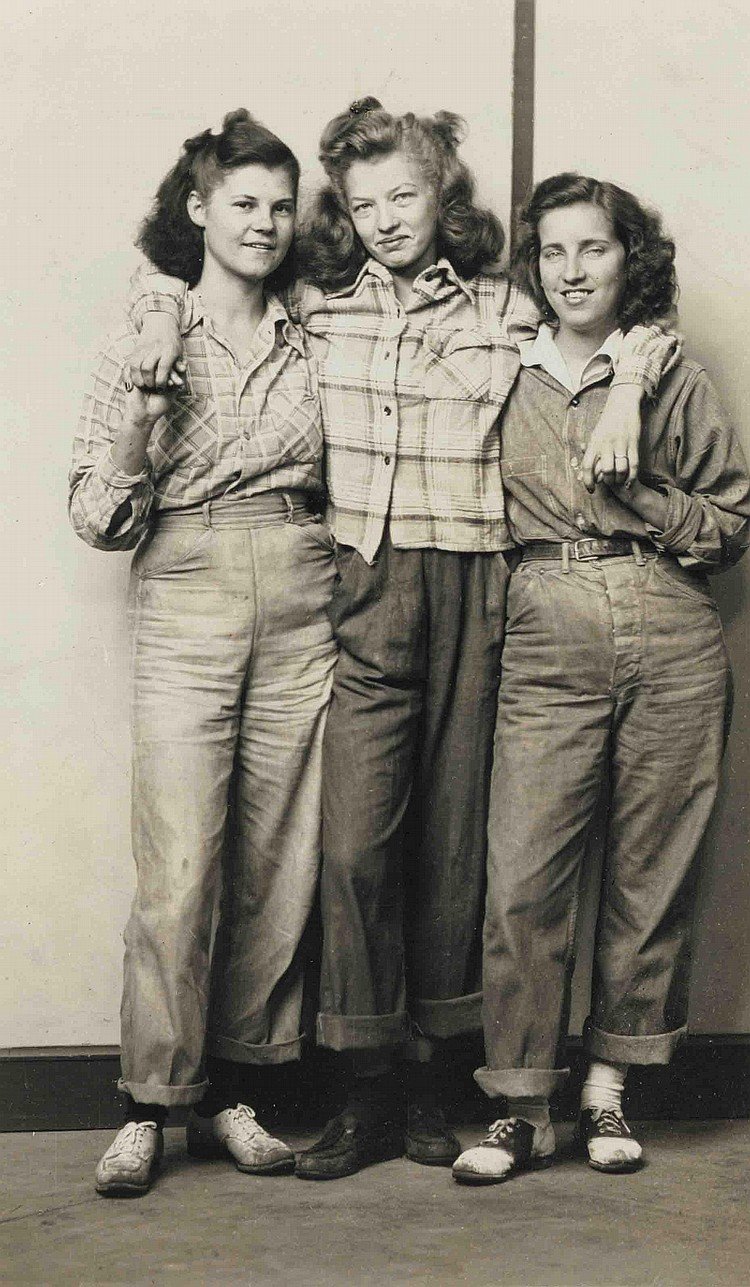

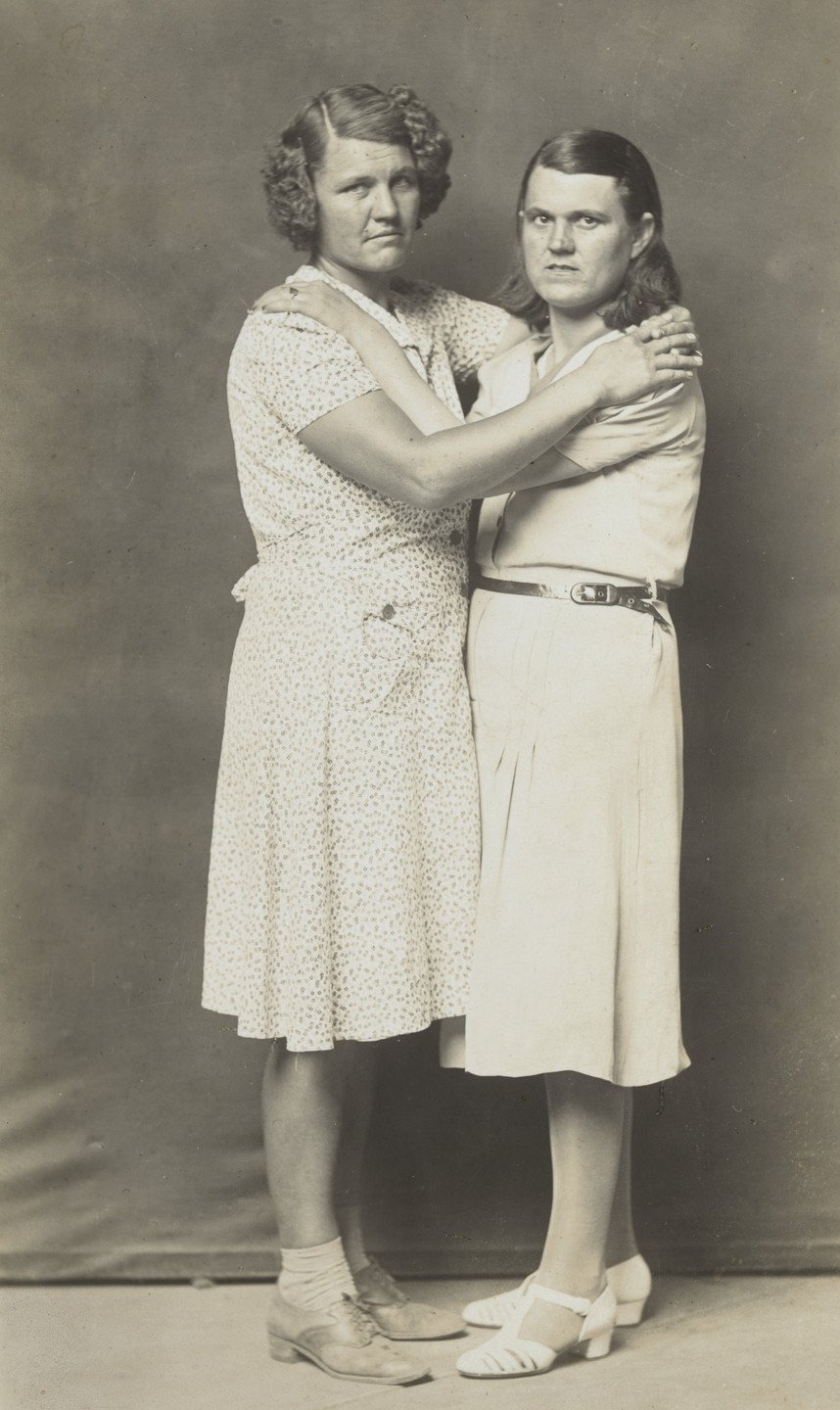

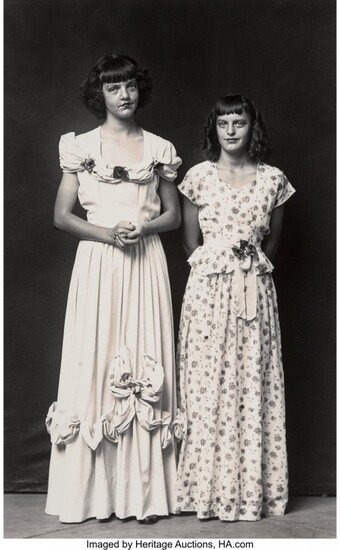

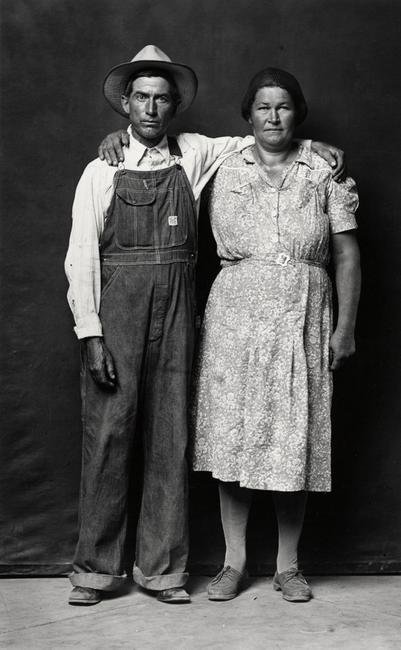

At the same time that the Rickert Studio was in operation, a photographer named Mike Disfarmer was working many miles south in Heber Springs, Arkansas. He was active in the 1940s and 50s, and would not gain any notoriety until years after his death, when photographs by Disfarmer began to be appreciated.

Mike Disfarmer left no will when he died and had no friends or family to take the contents of his studio. Thankfully these photographs were preserved for us to appreciate. They are truly revealing about American culture at a very specific time. Disfarmer’s unique style captured the eye of a few savvy people, leading to a race to locate them. They have found their way into collections worldwide.

Mike Disfarmer, 1884-1959

Finally, here are some images by Alan Pflieger, who saved the Rickert Studio negatives. He has been practicing photography his entire life. For many years he ran a photographic studio, documenting hundreds of weddings, engagements, anniversaries, board meetings, and more in northeastern Indiana. His best work, however, has been done while traveling the country with Colleen, toying with different types of cameras and experimenting with both digital and darkroom-based manipulation.

Episode 15: Post-Sale Wrap with Emile and Aimee

While we can’t gossip about EVERYTHING we want to, we do cover a fair amount in this episode, a special post-sale discussion about the 13 April Photographs auction at Sotheby’s.

In this discussion we start out with a quick post-sale report for the recent auction of A Grand Vision: The David H. Arrington Collection of Ansel Adams Photographs. Together with the first tranche of prints we sold from David’s collection in 2020, the sales were an amazing success (over $11 million in sales) and evidence of Adams continued popularity and strength of the market for his photographic prints.

Emily picked this beautiful, rare albumen print by Thomas Eakins as her favorite. At $30-50,000 as a pre-sale estimate it gathered plenty of attention and had a lot of bidding activity during the auction itself.

Thomas Eakins, Untitled (Male Nudes Boxing), sold for $327,600

Aimee chose this work by Diane Arbus, Girl with a Cigar in Washington Square Park, N. Y. C. from 1965 as a favorite. It is a very early print made by the photographer. It sold for $60,480 against the pre-sale estimate of $30,000-50,000.

Diane Arbus, Girl with a Cigar in Washington Square Park, N. Y. C., 1965

As we discuss in the episode, of my favorite photographers, Steven Arnold, was also represented by a piece in the sale. While his work doesn’t have a huge market, I try to include them when I can. A great film came out not too long ago about Arnold and it is definitely worth a watch. Visit his archive’s website for more information.

Episode 14: A Talk with Lee Marks

Lee Marks Fine Art is located in Shelbyville, Indiana, which makes her a fellow Hoosier now even though she’s originally from the East Coast. It’s an odd place to be a photography dealer, but Lee makes it look easy. Maybe that’s because she has so much experience working with artists, collectors, and colleagues in the business.

Lee Marks

Photo by Jim Smith

Lee works with the photographers she represents very closely, helping with the publication of a number of impressive photo books. She recently opened a show of stunning work by Lucinda Devlin.

Lucinda Devlin, Langjokull Glacier, Iceland #1, 2018, pigment inkjet print, from the ‘Subterranea’ series. Image © Lucinda Devlin

Lee was a founding member and past president of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD).

The past 5 presidents of AIPAD

(L-R)

Robert Klein

Stephen Bulger

Catherine Edelman

Lee Marks

Richard Moore

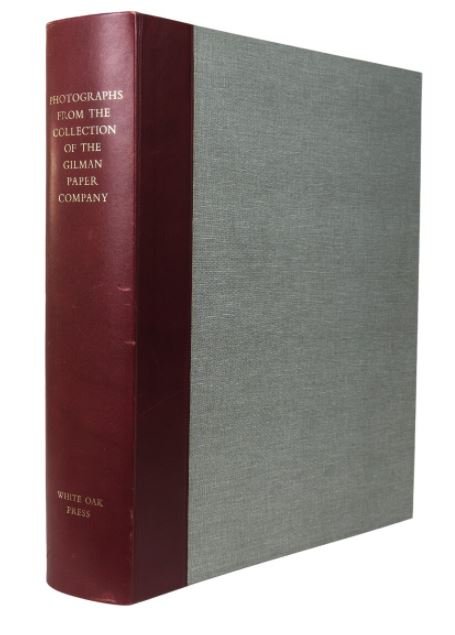

After earning a BA in Art History from Connecticut College, Marks spent eight years selling prints and photographs and organizing exhibitions at Marlborough Gallery, New York. While subsequently establishing her own business as an art dealer, she also became a consultant to Pierre Apraxine, Curator of the Gilman Paper Company Collection, and catalogued what was long considered the finest photography collection in private hands. She contributed the extensive plate-notes for Photographs from the Collection of the Gilman Paper Company (White Oak Press, 1985). In 2005 the Gilman Collection was acquired by New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As Lee says, looking at this book is a commitment.

Beginning in 1990 and over the next twenty years, Marks was consulting curator to the collector and former Dreyfus CEO, Howard Stein, and his foundation, Joy of Giving Something (JGS). The collection spans the history of photography, from the 1840s into the 21st century.

Sotheby’s held 175 Masterworks to Celebrate 175 Years of Photography: Property From the Joy of Giving Something Foundation on 11 December 2014, a memorable sale which made over $21 million dollars.

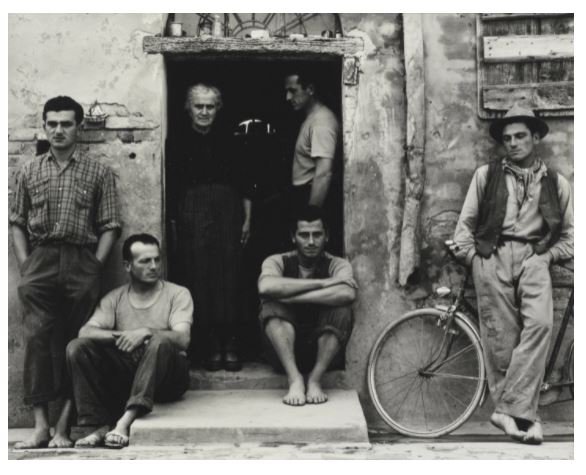

Paul Strand, The Family, Luzarra, Italy, sold for $281,000

Marks has co-authored photography publications with accompanying traveling exhibitions, including The Horse: Photographic Images, 1839 to the Present (Harry Abrams, 1991); New Realities: Hand-Colored Photography, 1839 to the Present (University of Wyoming Art Museum, 1997-98); Hope Photographs (Thames & Hudson, 1998), a book and exhibition of contemporary photographs circulated to ten US museum venues, 1998 through 2001; The Hidden Presence (Ceros / Librairie Plantureux, Paris, 2005), a collection of "hidden mother" tintypes; and "The Office/In and Out of the Box," shown at the Dorsky Gallery, New York City.

Episode 13: The Witch Dance

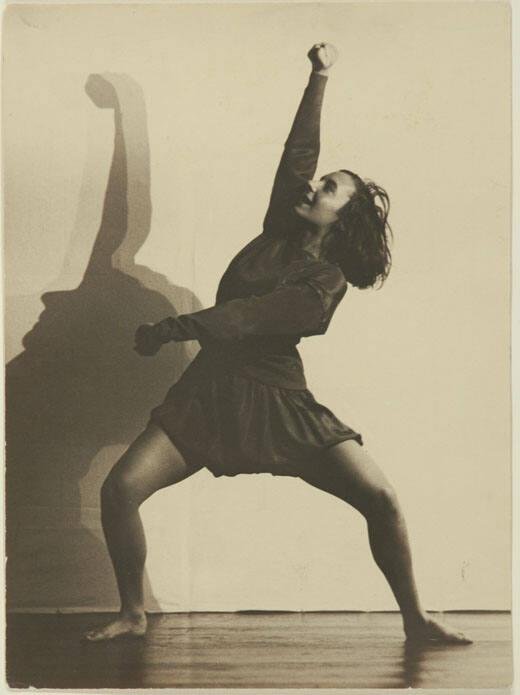

On March 17 Sotheby’s will sell a trio of images showing Mary Wigman performing her ‘Hexentanz’ (Witch Dance) in the 1920s by Charlotte Rudolph.

Charlotte Rudolph (1896 - 1983)

Untitled (Triptych of Mary Wigman in the Masked 'Witch Dance')

blind-stamped Ch. Rudolph Dresden (on each image)

3 gelatin silver prints on carte postale

5 ⅜ by 3 ½ in. (13.7 by 8.9 cm.) (each)

Executed circa 1926.

Mary Wigman (1886 - 1973) is considered by many to be the founder of modern dance in Europe. The Wigman School in Dresden produced many of the first generation of leading concert dancers in Germany; similar schools were later founded by Wigman in Berlin and New York.

Wigman and other modern dancers active in the 1920s and 30s were a huge inspiration for the chorography for the remake of Suspiria in 2018, directed by Luca Guadagnino.

Here is the original trailer for Suspiria from 1977, directed by Dario Argento. It’s…. very different from the remake.

Photograph by Charlotte Rudolph of other dancer, Gret Palucca, in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, circa 1928

Episode 12: Ansel Adams Detective

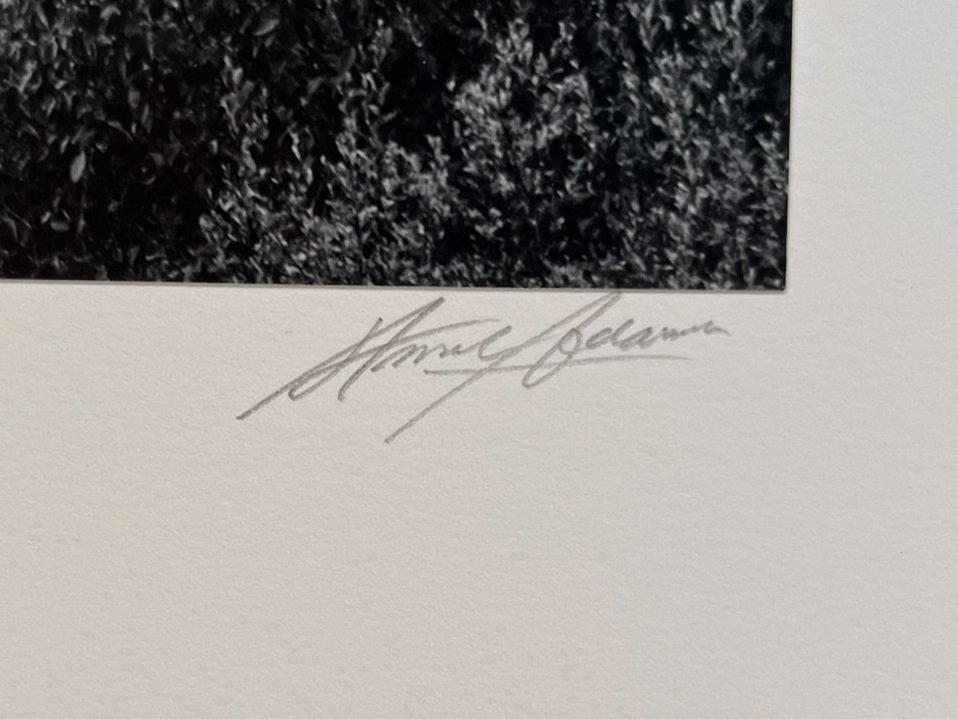

In this episode I give you my secret five-step process for analyzing Ansel Adams prints, providing lots of details on identifying print dates through paper type, stamps, and signature.

I have learned so much after looking at close to 1000 Ansel Adams prints thus far in my career. Many of which were in the collection of David Arrington, whose collection has been handled by Sotheby’s in two sales- one in 2020 and one in February 2022.

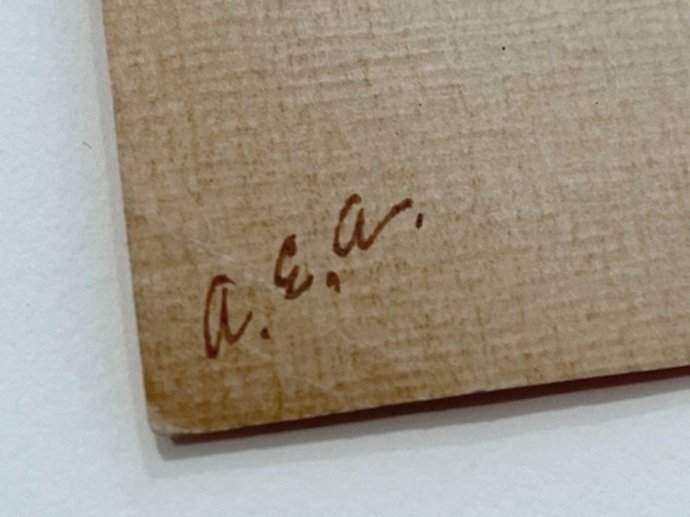

Here is an example of a label that Adams used between 1936 to 1944, as well as a Michael and Jeanne Adams collection stamp.

Here is a close up of the special, vellum-like, pearlescent paper that Adams used for his ‘Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras’ portfolio. You can also see a little deposit of original retouching at the center right of the image.

Adams used a very shiny board to mount his prints in the early part of his career.

This is very early print (1920), Lost Valley, Yosemite, is on golden-toned, heavy-weight paper with a subtle texture. It is then mounted on a piece of heavily textured ivory paper.

This is a very typical presentation for a 1970’s print- trimmed to the image, mounted to heavy white board, signed in pencil under the image on the mount, and stamped on the reverse.

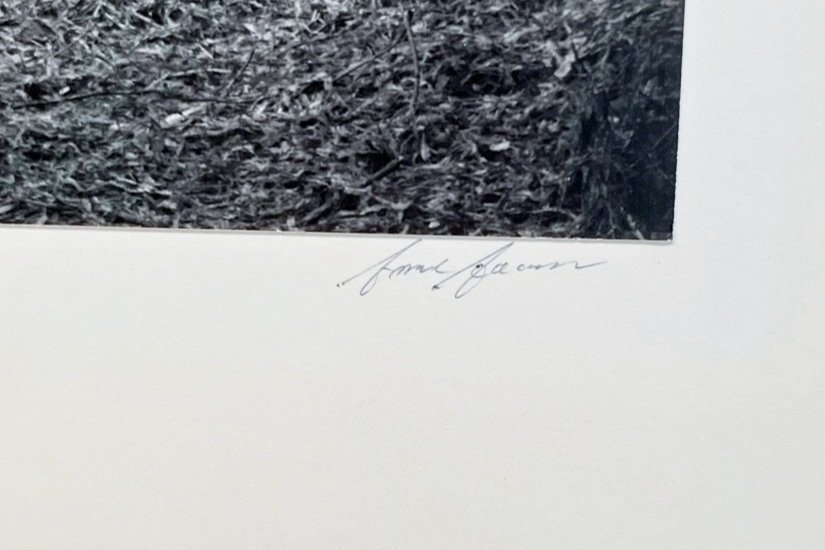

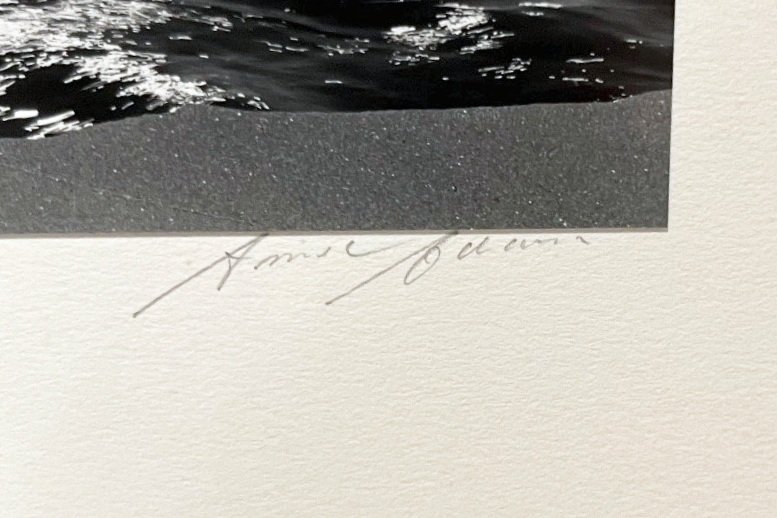

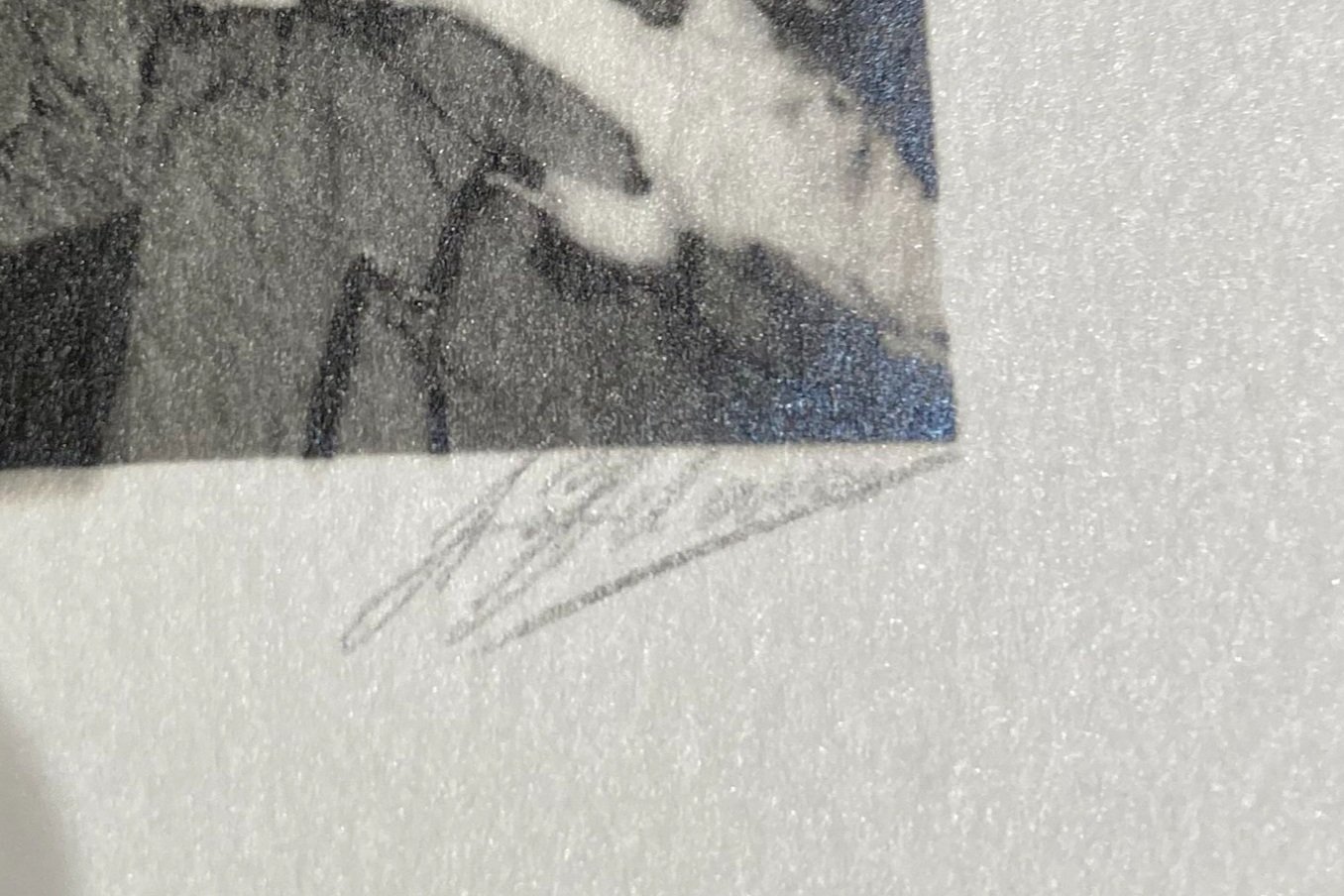

Adams’ signature changed a lot over the years, as you can see from the images below.

Photographer Alan Ross worked as Ansel Adams’ assistant and has put together an absolutely fascinating website with information about Ansel Adams’ working process.

Episode 10/11: Interview with Deborah Bell, Part I

After 13 years as a private dealer, Deborah Bell opened her first public gallery at 511 West 25th Street in Chelsea and remained there for 10 years (2001-2011). In 2011 Bell closed the gallery in order to join Christie’s New York, where she was Head of the Photographs Department for 2-1/2 years. In 2014 she re-established Deborah Bell Photographs, and in April 2015 moved to the gallery’s present location on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Bell’s professional career as a dealer began with a position at the Sander Gallery, New York, in 1984. She then joined the Prints & Photographs Department of Marlborough Gallery in 1985, and from 1986-87 worked with the Estate of Marcel Broodthaers in Brussels, Belgium. From 1988-1990 Bell assisted Richard Pare, Founding Curator of Photographs for the Canadian Centre for Architecture and the Seagram Collection, New York.

August Sander, Bricklayer, 1928, Minneapolis Institute of Art

A native of Minnesota, Bell received a BFA in Photography from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 1976, and an MA in Art History from Hunter College in 1984. Before and after relocating to New York in 1978, Bell was a practicing photographer, and worked in editorial and commercial photography as a black-and-white printer and studio assistant.

From 1971-77, during her high school and college years in Minnesota, Bell was a docent and assistant-at-large at the Walker Art Center. From 1991-96 she was an adjunct professor of the History of Photography at the School of Visual Arts, New York.

Deborah Bell, image courtesy FK Magazine

One of the photographs that Deborah works closely with, Marcia Resnick, will have a traveling solo exhibition that opens at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art on 24 February.

Deborah has been a long time member of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers. The Association of International Photography Art Dealers encourages public support of fine art photography by acting as a collective voice for the dealers in fine art photography and through communication and education that enhances the confidence of the public, museums, institutions and others in responsible fine art photography dealers.

Episode 9: If You Could Read My Mind, Love

Ted Serios and Dr. Jule Eisenbud tried to convince the world that Ted had extraordinary powers- a special gift that allowed him to think super hard. He could think his thoughts with such voracity that they could travel through space and into a camera so they could be recorded on film. Unfortunately, Ted did not have special gifts. He did have a “gizmo” (his term, not mine) that acted as a tiny lens in order to reflect an image that the camera would pick up. Pretty clever, but not failproof- and something people eventually caught on to.

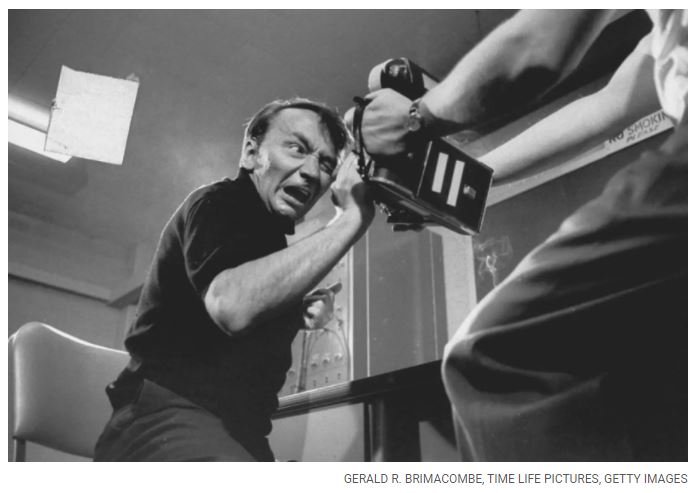

Here’s a picture of Ted Serios thinking really, really, really hard.

Jule Eisenbud (l) and Ted Serios

Here are a few of Ted’s ‘thoughtographs’ (Collection of University of Maryland, Baltimore County):

Here is a photo by Anton Guilo and Arturo Bragaglia that we sold at Sotheby’s in April of 2020 for $100,000 (against the pre-sale estimate of $50,000-70,000!) the Bragaglia brothers were Futurist filmmakers, writers, and artists. They created an amazing body of work and I really dug into the research on this one. Click here learn more.

UN GESTO DEL CAPO, 1911

Episode 8: Diane Arbus, Steven Shainberg and ‘Fur’

Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus (also known simply as Fur) riled a lot of people up when it was released in 2006. Here is the trailer:

Director Steven Shainberg has been interested in Arbus his entire life, and knew that making a straight biopic was not going to cut it. He chose instead to focus on just a few days of Arbus’ life (and added a fairy tale element).

Episode 7: Diane Arbus and the Monster Club

In this episode, I tell the story of how I got to research a very rare photograph by Diane Arbus that she took while on assignment for a magazine called Famous Monsters of Filmland. The photograph features 5 youngsters on the stoop of their rowhouse in Queens, sporting monster masks. It was was sold at Sotheby’s on 3 October 2019.

It sold for $50,000 against a pre-sale estimate of $15,000-25,000!

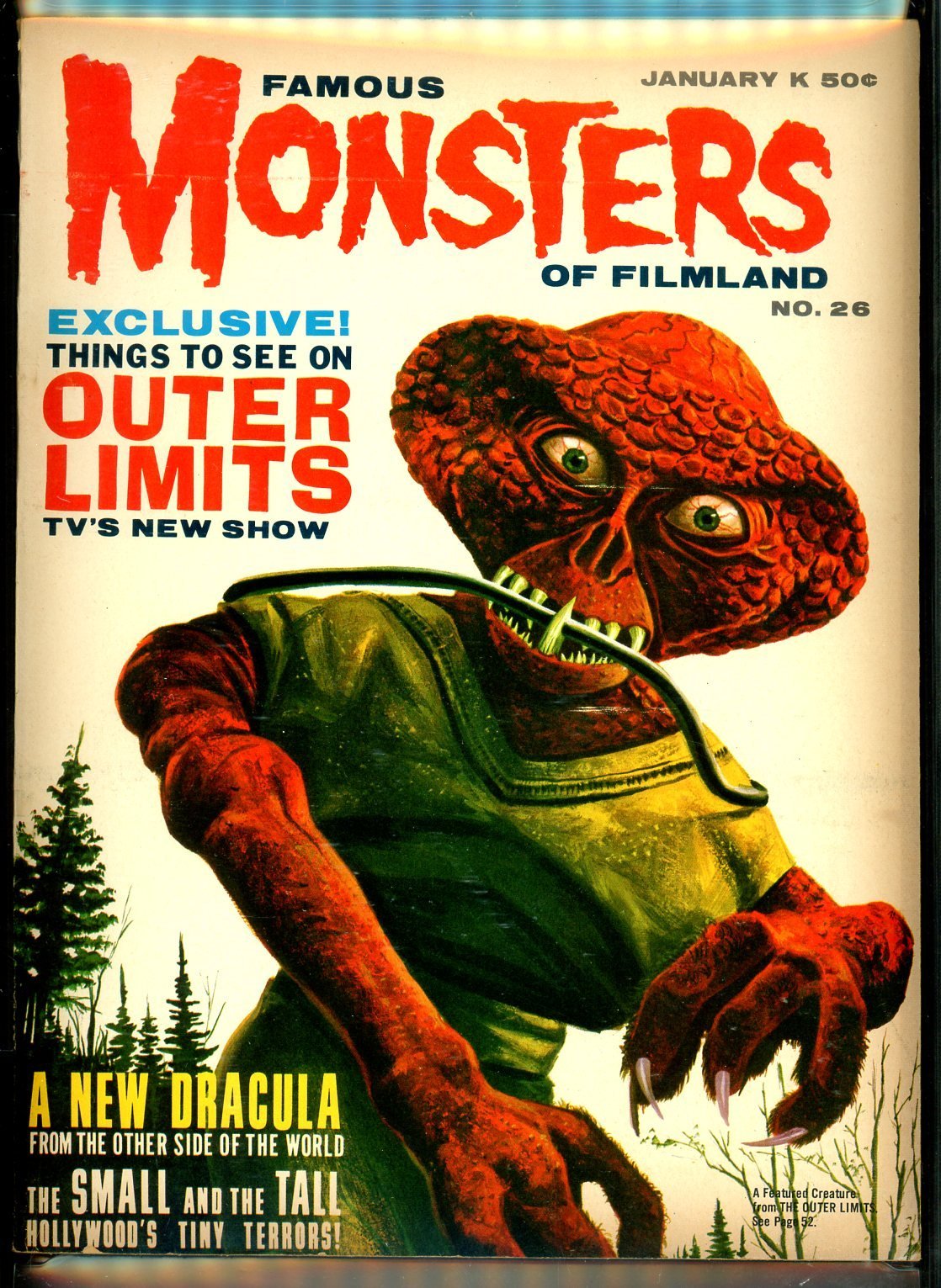

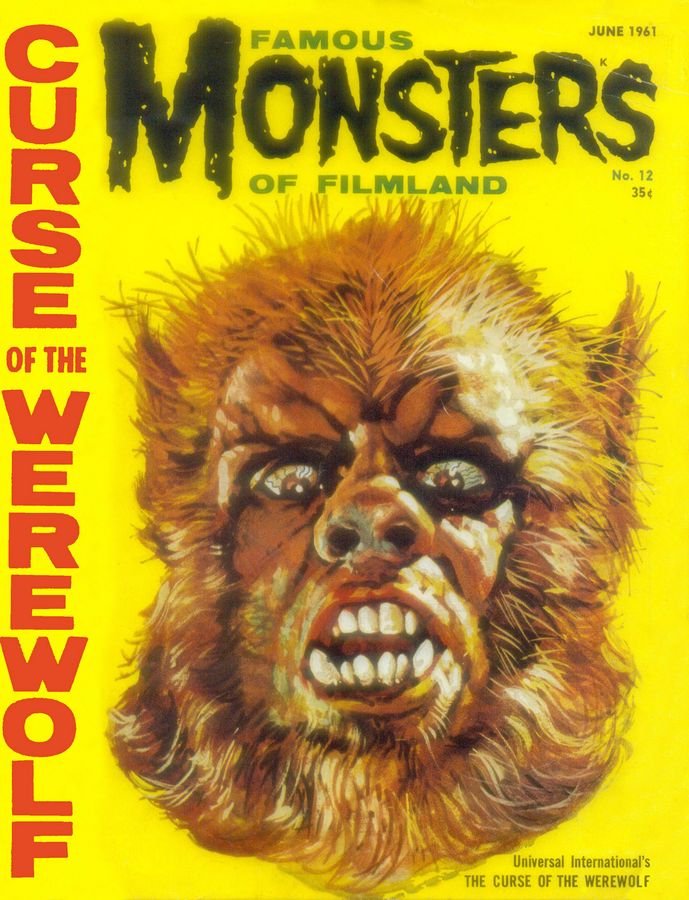

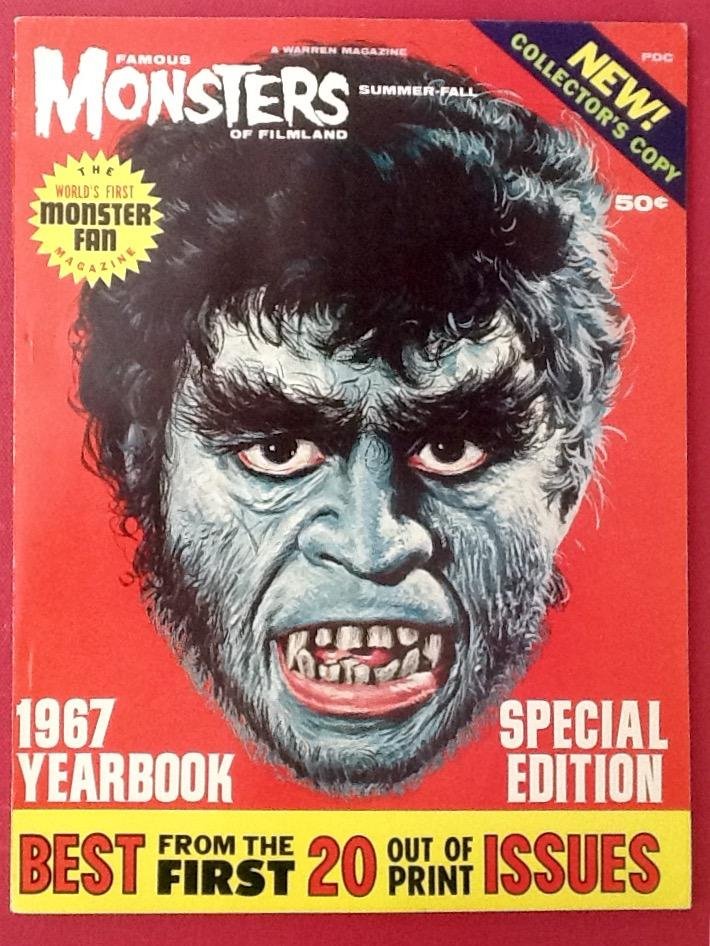

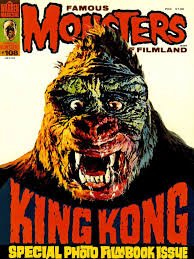

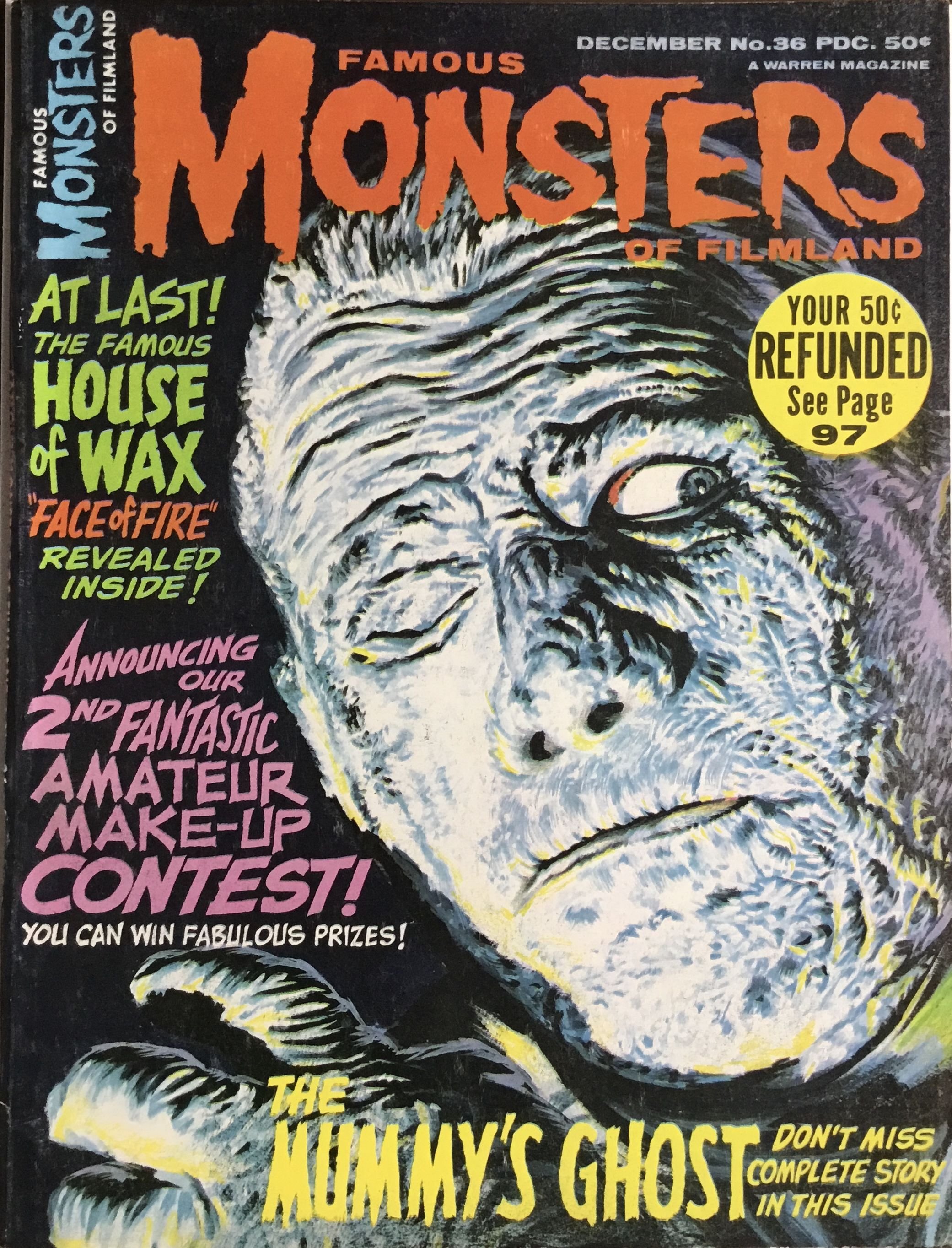

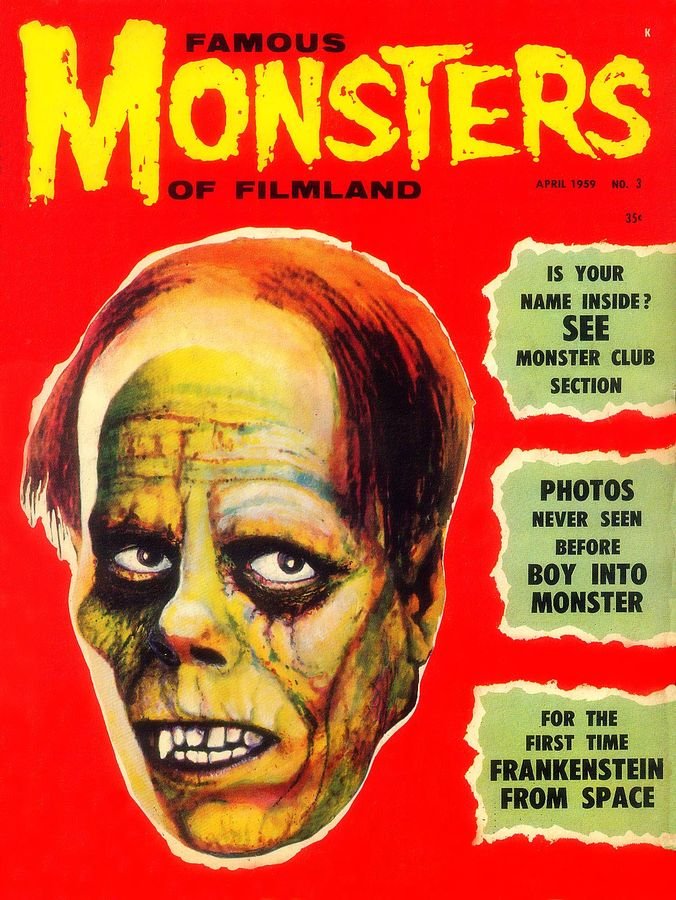

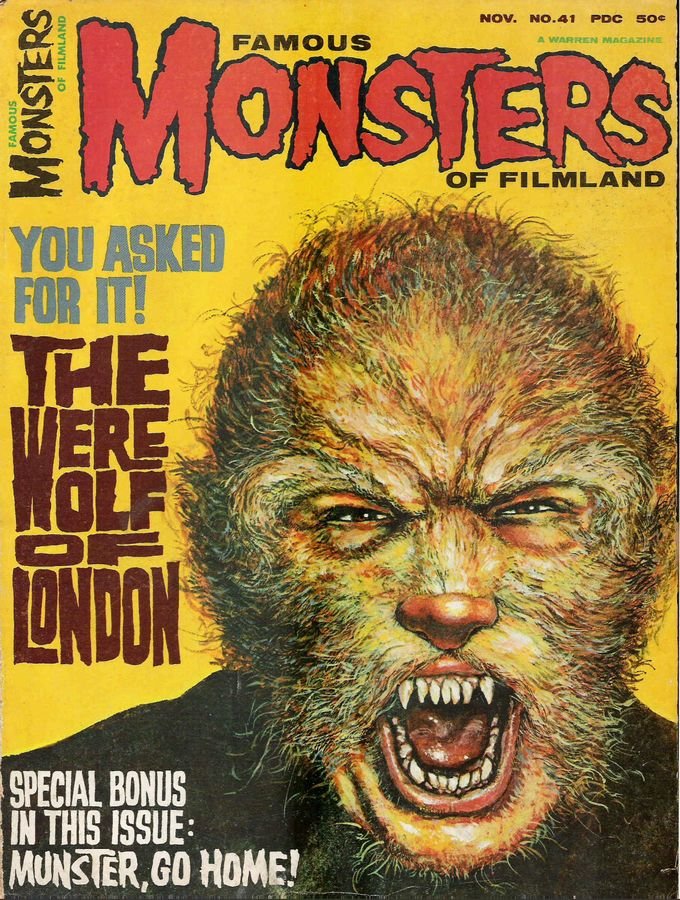

Jim Warren and editor Forrest Ackerman started publication of Famous Monsters of Filmland in 1958 and it was still in production until 1983. Here are some of my favorite covers:

Episode 6: Devil’s Paradise: The Problem with Rubber

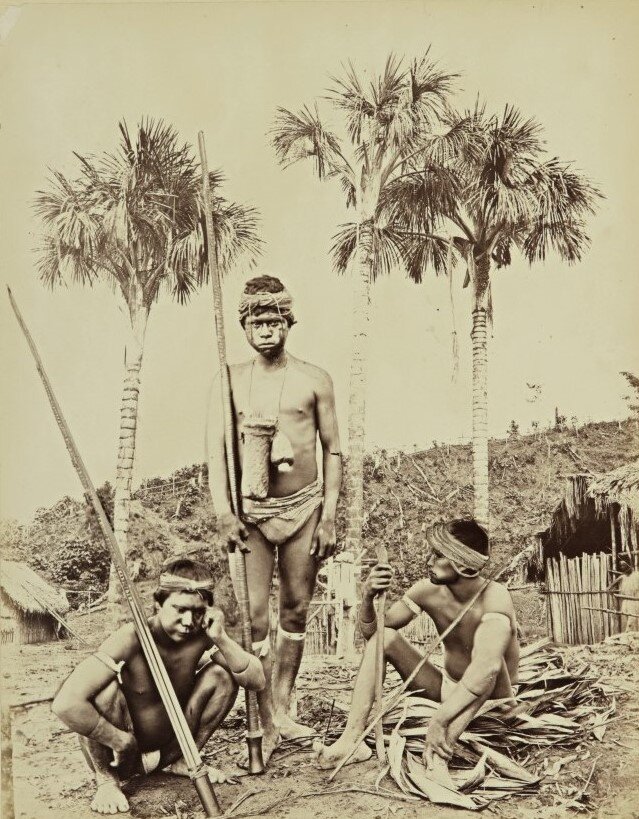

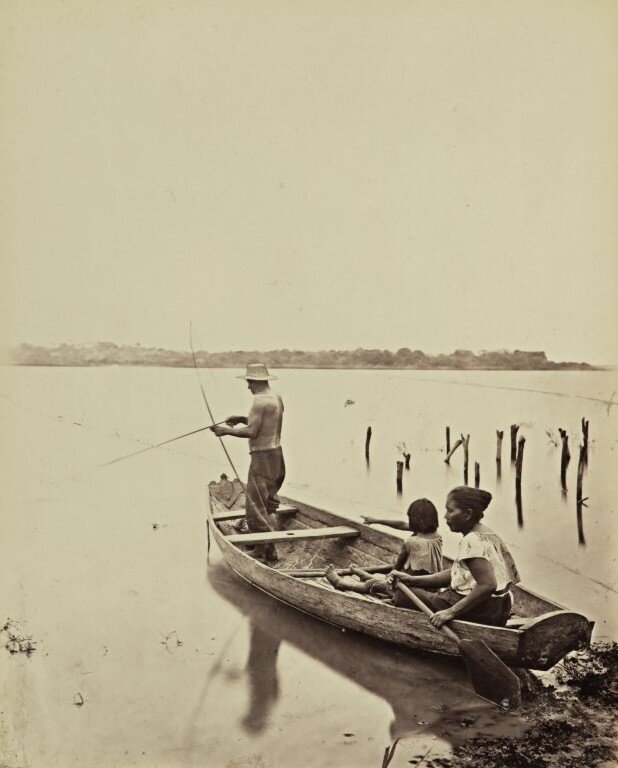

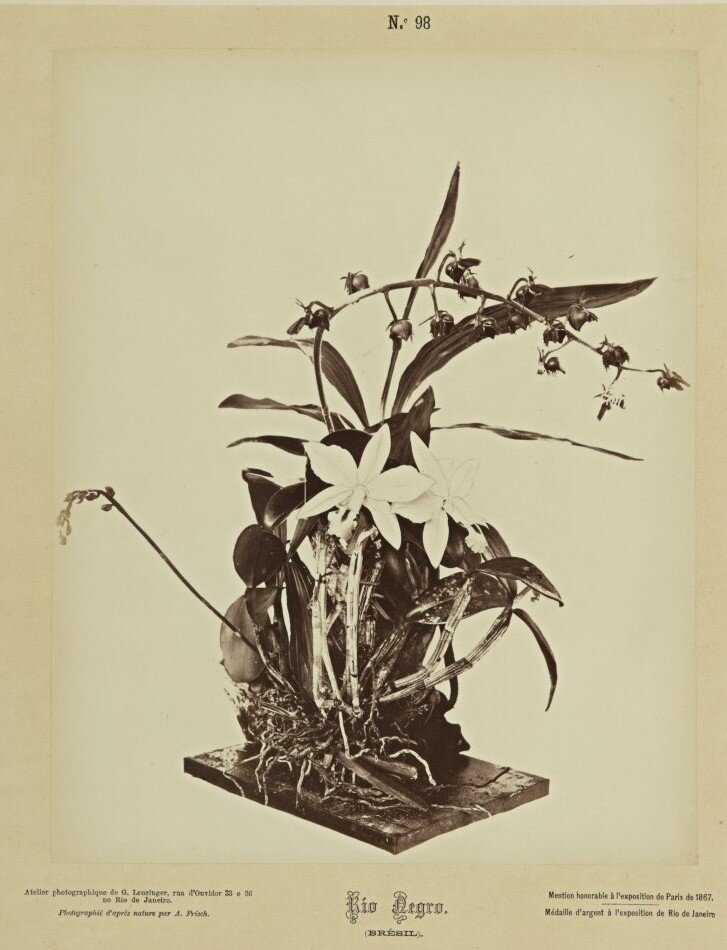

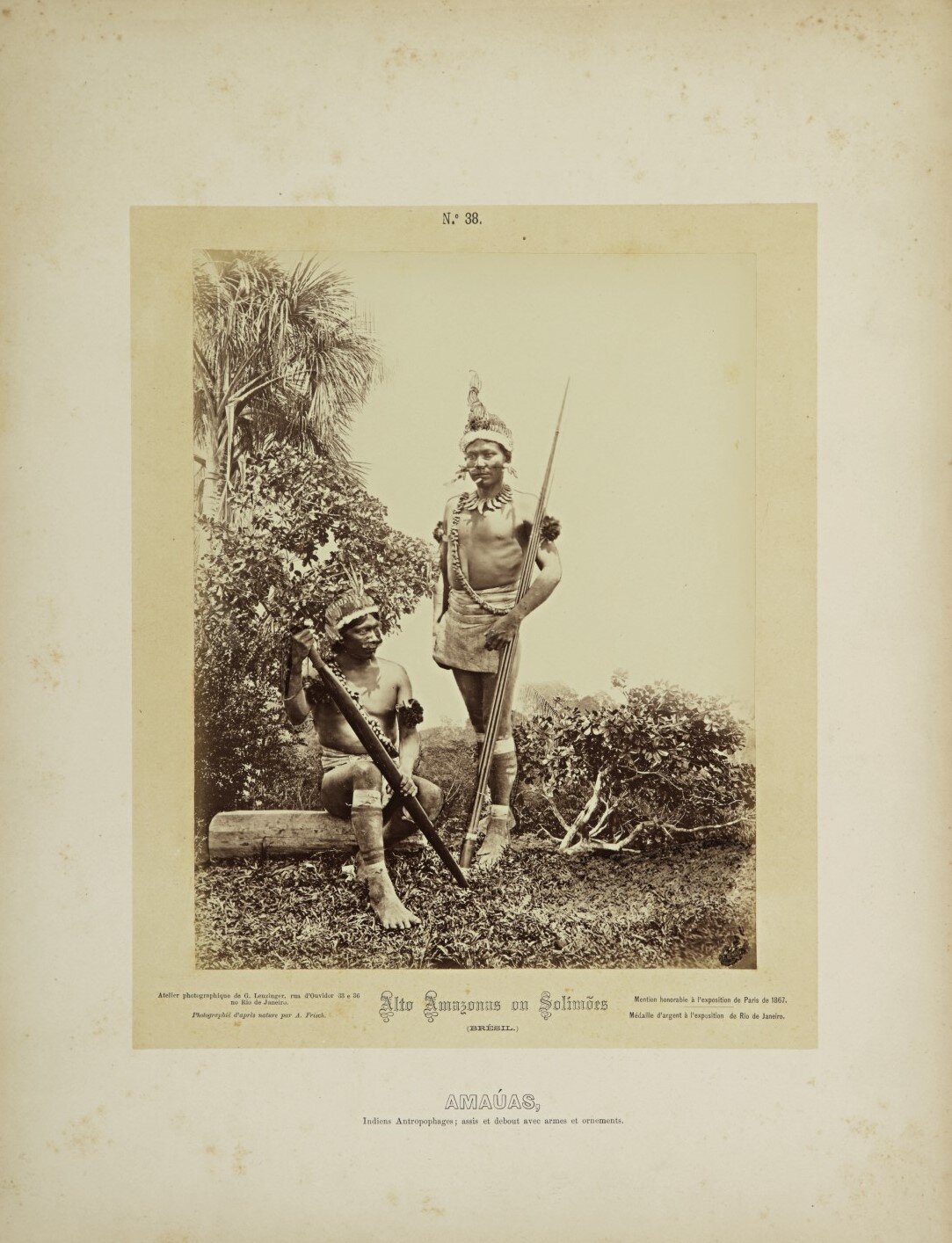

In this episode, I tell the story of a photographer named Albert Frisch, a German photographer who was on assignment to photograph the landscape and people of the Upper Amazon. Coincidentally, another adventurer had followed his route only a few years before by the name of Henry Bates, who wrote a book about his adventures when he returned to England.

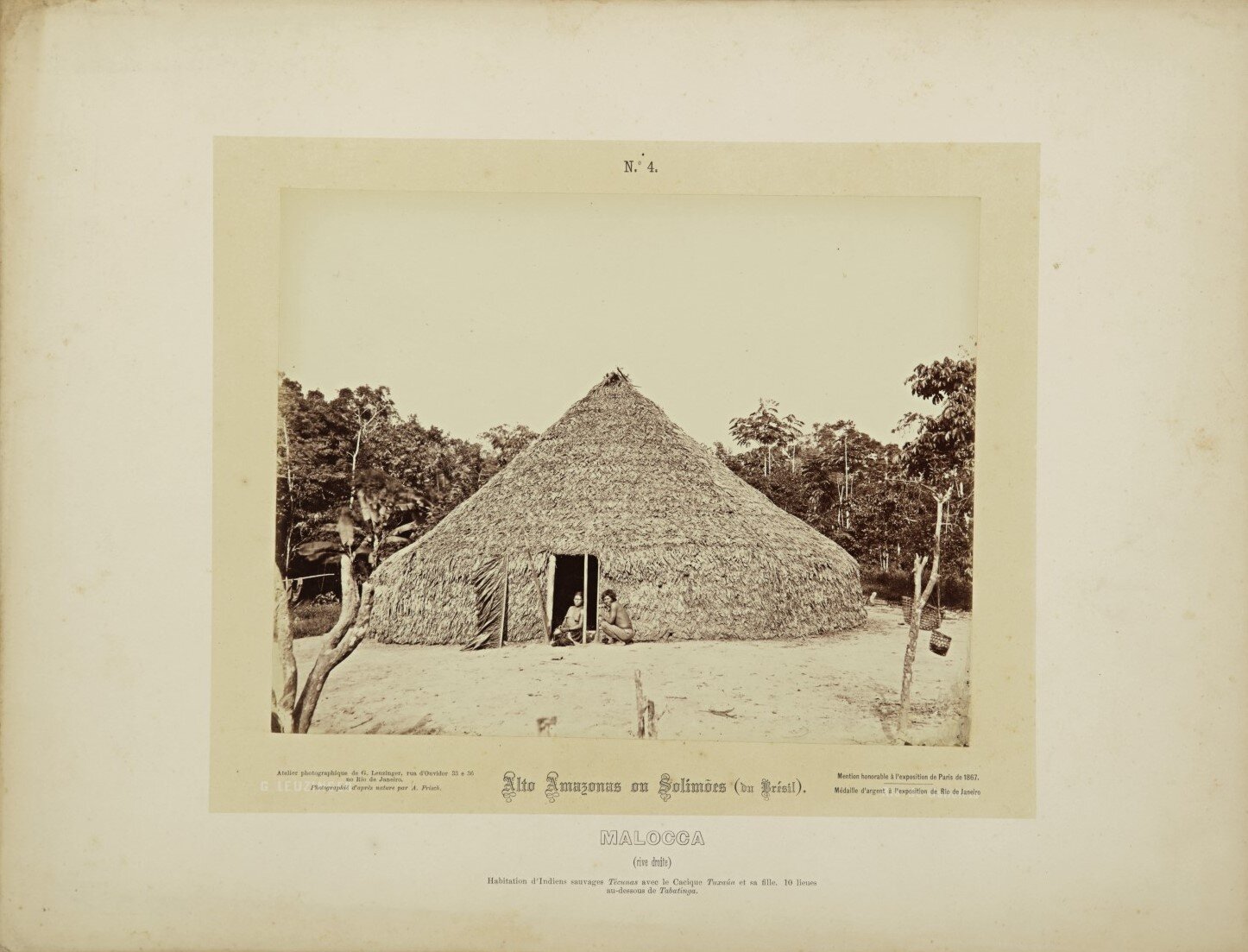

All images are from Albert Frisch’s portfolio, Résultat d’une expédition photographique sur le Solimões ou Alto Amazonas et Rio Negro, 1867-68, printed in 1869

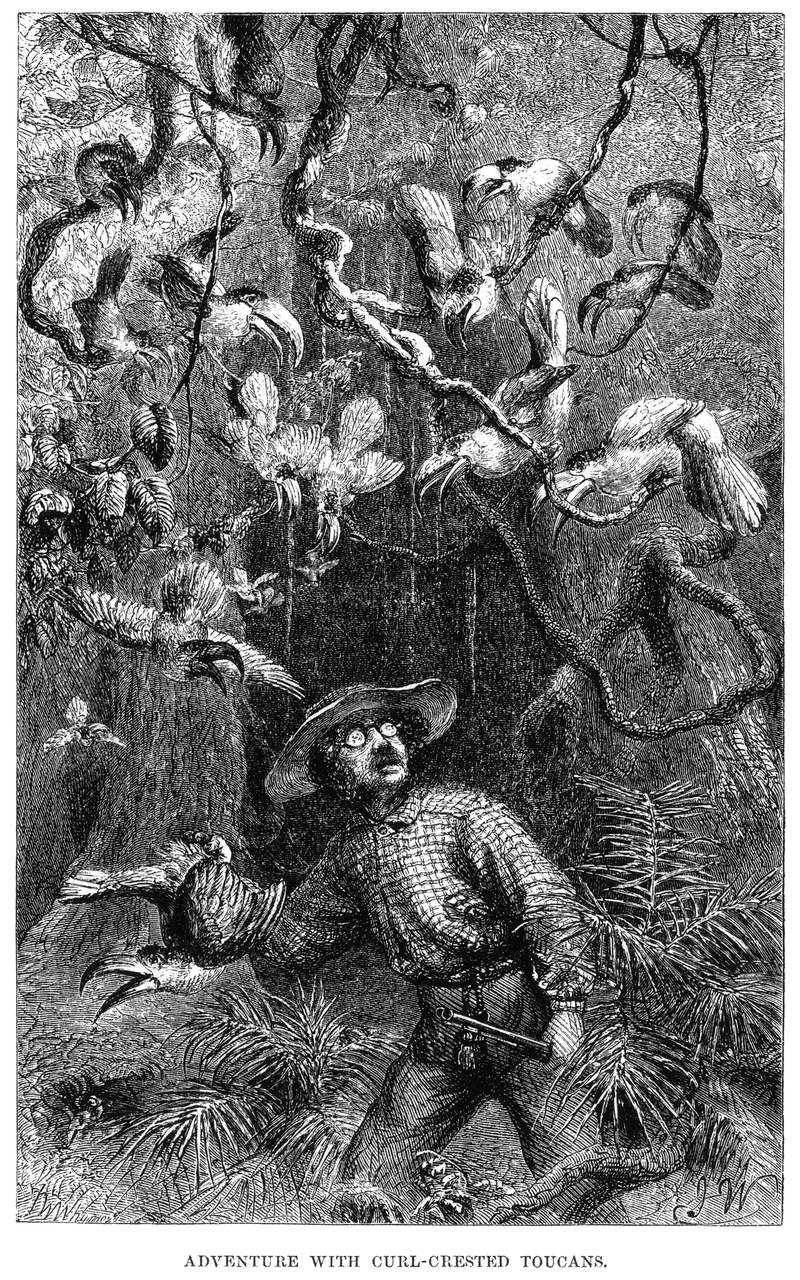

Frontispiece illustration for Henry Walter Bates’ The Naturalist on the River Amazons: A Record of the Adventures, Habits of Animals, Sketches of Brazilian and Indian Life, and Aspects of Nature under the Equator, during Eleven Years of Travel (London, 1863)

I used Henry Bates’ journal as a way to understand what it was like to travel on the Amazon.

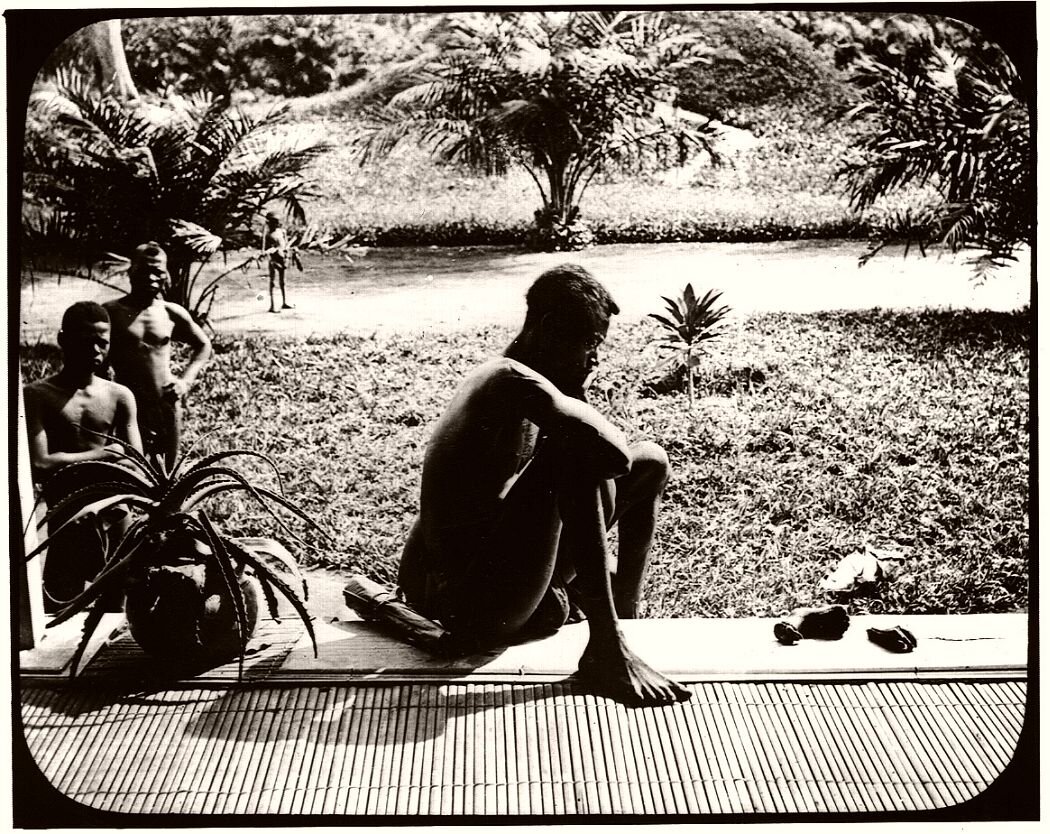

Albert Frisch, Résultat d’une expédition photographique sur le Solimões ou Alto Amazonas et Rio Negro, No. 68 – Alto Amazonas ou Solimões (Brésil). Fabrication de Caoutchouc, 1867-68, printed in 1869

A rubber shoe, 1830s, Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Ontario

I made a map of Bates and Frisch’s journey and it is shown below. Frisch’s trip is in blue, while Bates is in red. A the majority of prints that were sold by Frisch when he returned were to tourists, but it is not too far of a stretch to imagine that his photographs may have also been of interest to naturalists like Bates.

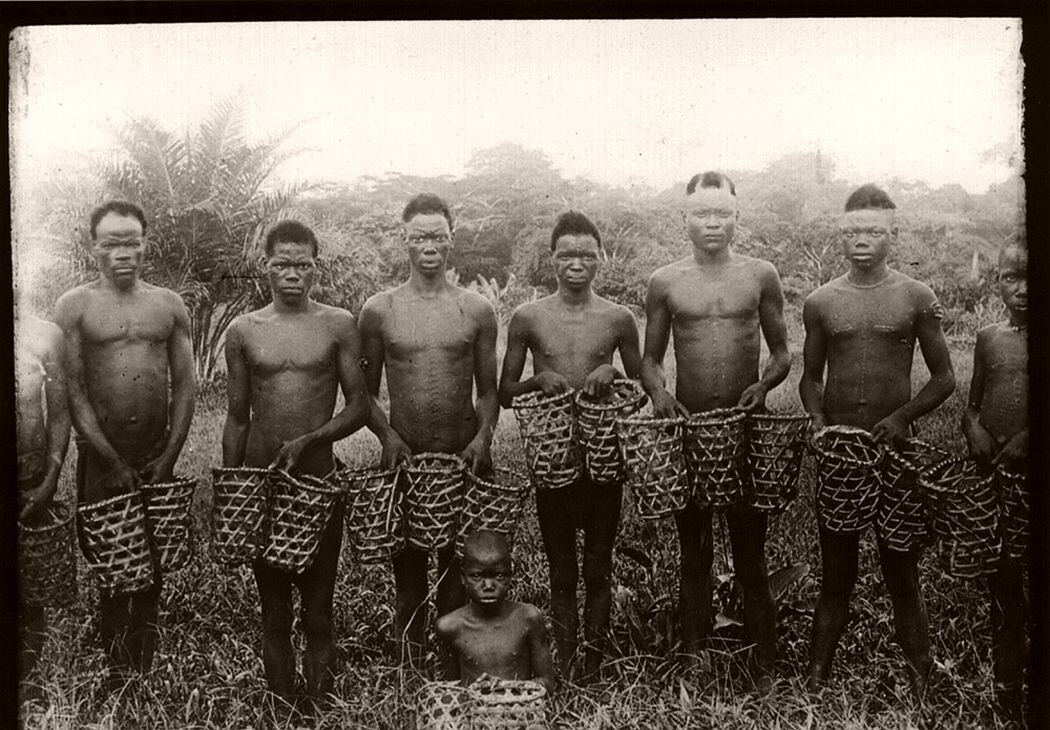

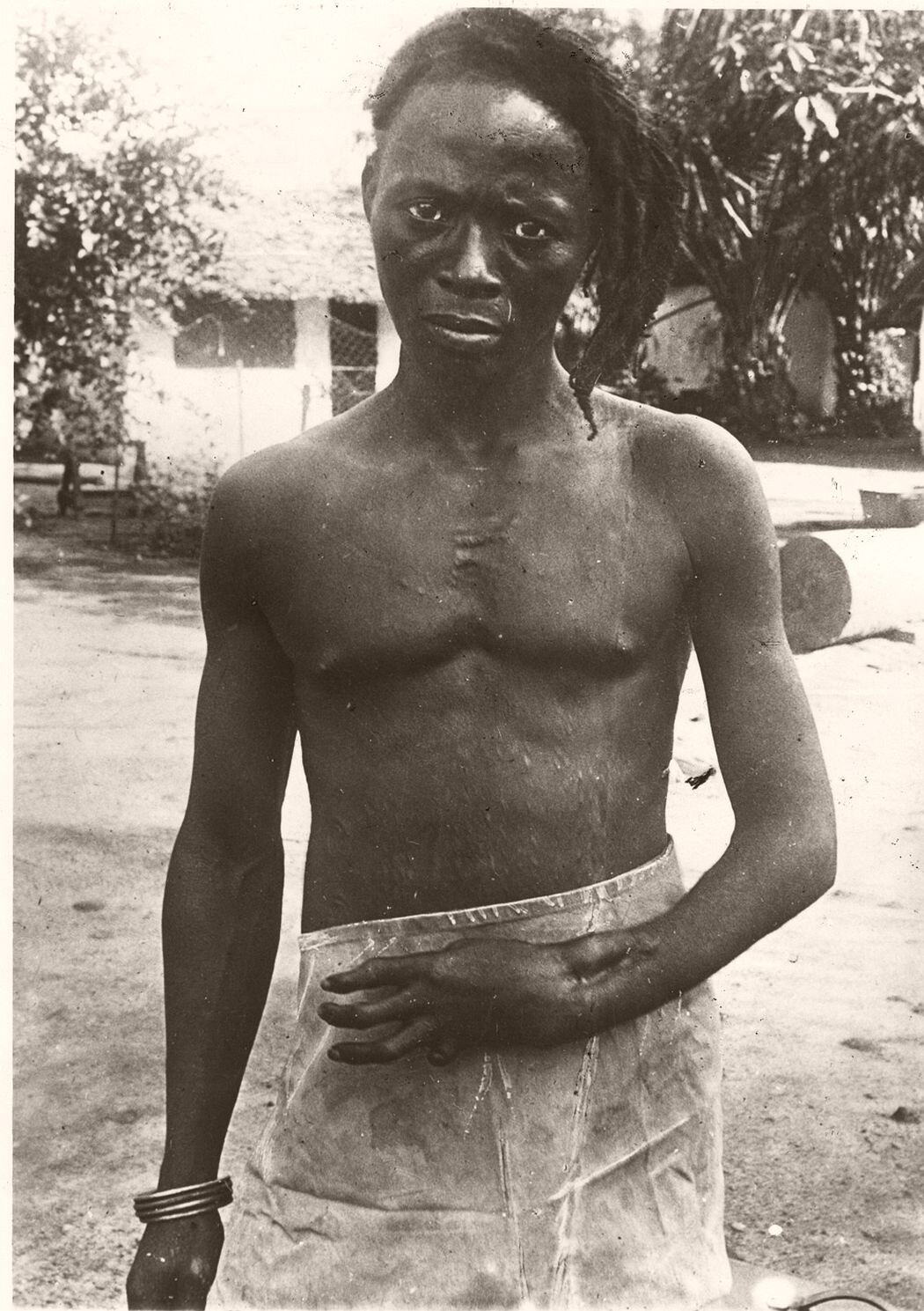

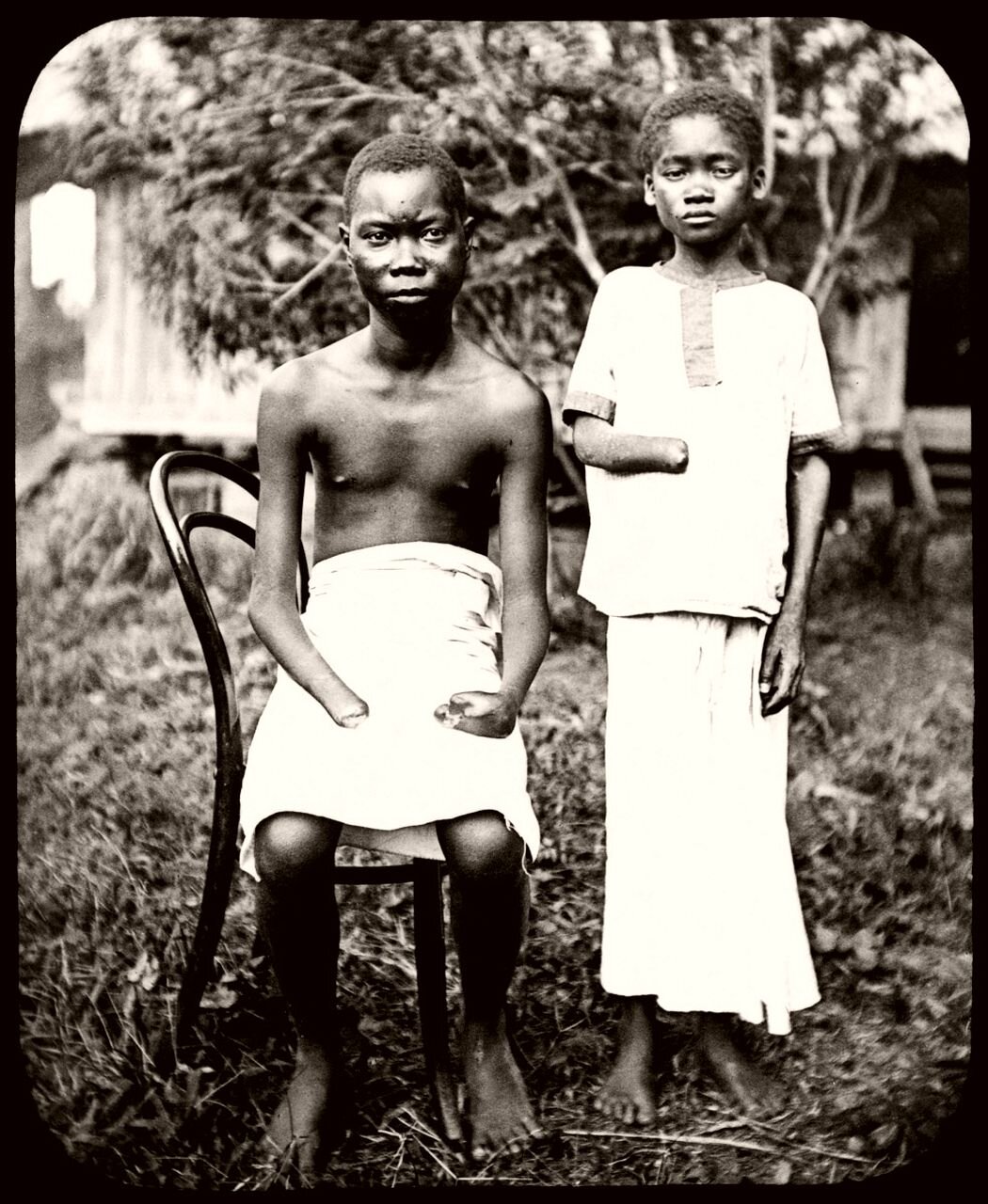

Unfortunately, the quest for rubber was a bloody pursuit, affecting not only the Brazilian rainforest but also the so-called Belgian Congo.

Photographs by Alice Seely Harris illuminated what was happening to the people being oppressed by this bloody system.

Sources used for this episode:

Henry Walter Bates, The Naturalist on the River Amazons: A Record of the Adventures, Habits of Animals, Sketches of Brazilian and Indian Life, and Aspects of Nature under the Equator, during Eleven Years of Travel (London, 1863)

Walter Hardenburg, The Putumayo, The Devil's Paradise: Travels in the Peruvian Amazon Region and an Account of the Atrocities Committed upon the Indians Therein (London, 1912)

T.J. Thompson, "Light on the Dark Continent: The Photography of Alice Seely Harris and the Congo Atrocities of the Early Twentieth Century,” International Bulletin of International Research, 1 October, 2002, Vol. 26, Issue 4, pp. 146-149

Manuela Fischer and Michael Kraus, eds.., Exploring the Archive: Historical Photograph[s] from Latin America, The Collection of the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, 2015

Mark Meuwese, Brothers in Arms, Partners in Trade: Dutch-indigenous Alliances in the Atlantic World, 1595-1674 (Leiden, 2012)

Episode 5: The Monkey on Her Back

In 1939, LIFE photojournalist Hansel Mieth took a photograph that would haunt her for the rest of her life. That photograph was … of a monkey.

In this episode, Aimee talks about the time she handled a print of this image and the surprising history behind it.

The photograph discussed in Episode 5 is Hansel Mieth’s iconic shot of a Rhesus Macaque monkey sitting off the waters of Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico. This particular print- a rare vintage image- was featured in an auction called 50 Masterworks to Celebrate 50 Years of Sotheby’s Photographs, on 21 April 2021.

This is the back of the photo. You can see the photographer’s credit stamp, signature, and date.

In the 16 January 1939 issue, LIFE magazine published this image as ‘The Picture of the Week.’ Mieth later recounted the making of the portrait:

“One afternoon all the doctors were away, and a little kid came running to me and said, ‘A monkey’s in the water.’ I came down, and that monkey was really going hell-bent for something. ‘He is not coming back,’ I said. ‘I better go in and get him’. . . I threw my Rolleiflex on my back and swam out. . .Finally, I was facing the monkey. I don’t think he liked me, but he sat on that coral reef there, and I took about a dozen shots.”

(as quoted in Unfinished Stories, pp 38 and 40)

LIFE Magazine, 16 January 1939 issue.

Hermione Sharp, my colleague in the Photographs department at Sotheby’s, was the key researcher on this photograph for the auction, and in her essay she wrote:

“LIFE editors captioned this image ‘A misogynist seeks solitude in the Caribbean off Puerto Rico,’ immediately imbuing it with humor and lightheartedness. One of the writers had decided that publishing magnate Henry Luce resembled the monkey when angry – which quickly became an inside joke among staff. The narrative printed alongside the image was also problematic and somewhat misleading. It explained that the male macaque ran from the jungle into the water, which rhesus monkeys typically avoided, in order to escape the raucous chatter of the female monkeys. This not only played into the blithe ‘misogynist’ label, but also oversimplified the complex research being conducted on the island. Mieth cared deeply for the animals and had immense admiration for the scientists’ work. Mieth often referred to this photograph as ‘the monkey on my back.’ Despite its popularity after its initial publication, Mieth felt ambivalent, if not downright negative, about it because of the way it was appropriated.”

Mieth and Hagel were tireless in their photographic endeavors, documenting the “Hoovervilles” around Sacramento and San Francisco, as well as the plight of migrant workers, longshoremen, and dockworkers. On assignment for LIFE, Mieth also documented life in the Heart Mountain Japanese-American internment camp. Together, Hagel and Mieth worked on a series documenting the lives of the Pomo Indians, an American Indian tribe indigenous to Sonoma County, California.

You can learn more about Hansel Mieth and her husband, Otto Hagel, by visiting the website for the Center for Creative Photography. They hold the couple’s archives and many images are online.

The Hansel Mieth Prize is awarded every year to a photojournalist who has defied pressures or threats from prominent lobbying groups.